Who Tells Your Story? Some Reflections on America's Historical Landscape

What is the role of our national monuments, historical sites, and memorials in an era of anti-intellectualism?

If you have an eye for it, a rich landscape of early American history rolls out before you as you drive east through western Tennessee, through the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, across Virginia and into Washington, D.C. This summer my husband and I took our two sons (ages 8 and 11) and ventured east to the Appalachians, taking a trip my husband (also an historian) has always wanted to make to a part of the country littered with the estates of former Presidents, Civil War battlefields, museums, national monuments, and historical sites. Our Google Map skills are strong—I doubt we missed even one historical site of significance (most primarily White-centered) on our 665-mile road trip from Nashville to Washington, D.C.

On my last trip to Virginia, I was a twenty-year-old undergraduate and spending a summer at an archaeology field school on the Eastern Shore. That summer we made the most of our time and when we weren’t carefully excavating colonial post-holes, we visited surrounding historically significant places like Jamestown and Colonial Williamsburg. I remember how much I enjoyed those side trips, having always found colonial America a fascinating period of history. At the time I was caught up in the idea of standing in these places where defining events in American (and ultimately world) history unfolded, buying into the myopic established narrative of an exceptional America that struggled and overcame tyranny and injustice. Throughout my family’s trip this summer, I couldn’t help but reflect on how different my early adulthood, pre-9/11 experience of this landscape of American history was from my experience this year, over two decades later.

In particular, the social and political turbulence of the last seven years have highlighted the complexity and problematic nature of America’s historical narratives. Similar to the intellectual journey Kara describes in the opening chapter of The Good Kings, in which she recounts her recovery and breakaway from the cult-like comfort of traditional patriarchal Egyptological narratives, recent years have caused me to recognize the gaping holes in my understanding of American history created by an unquestioning acceptance of the historical assumptions reinforced by the prevailing privileged narratives and the absence of the intentionally suppressed histories that those in power wanted forgotten. In societies throughout history, part of the way people tell their stories and pass them on to future generations is through monuments, memorials, and (in more modern times) cultural heritage sites. My experiences this summer made me reflect on the role of American national historic sites, monuments, and memorials—how they are meant to help us write a national history and shore up national ideals and identity, and whether they can play a useful role in an America that is only just beginning to reckon with the complex and contradictory nature of its past.

Everyone is familiar with the old adage that history is written by the winners, and the winners (i.e. those who possess power) are always eager to write their history into the landscape with monuments and memorials. From the temples of ancient Egypt to the monuments of Washington, D.C., the common thread is the desire to present a straight-forward, uncontradicted version of history that can be experienced in a physical form. Anyone who has visited a historical site, museum, monument, or memorial can understand how that physical experience can be powerful and memorable. Having seen so many such places back-to-back this summer, I was struck by the variety of approaches and historical perspectives presented. Like American history itself, the inconsistency and contradiction could be dizzying. Given that many of the sights we were seeing were related to colonial and Civil War history, their stories were all thoroughly interwoven with slavery in America even though each place we visited dealt with this subject differently. For instance, the ways in which the estates of former slave-holding Presidents handled the juxtaposition of the devastating realities of slavery while elevating and honoring a slave-owning former President as a historical figure reflected an entire spectrum of approaches.

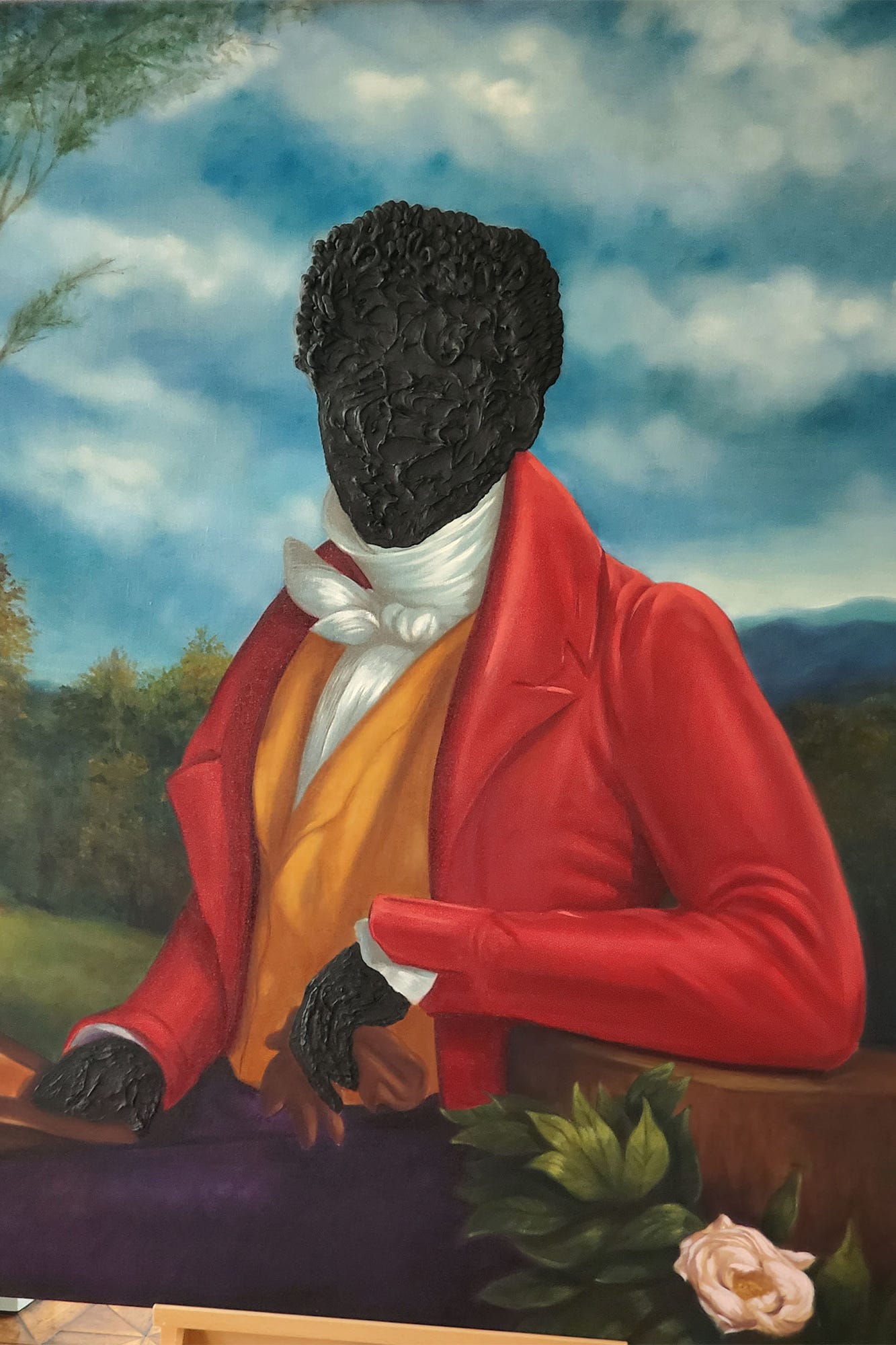

Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage made a minimal effort to discuss slavery, and the Trail of Tears was relegated to one sentence on a wall text panel. George Washington’s Mount Vernon and James Monroe’s Highland also did not prominently feature discussions of slavery. The best discussions of slavery in which visitors were actively encouraged to engage the subject were at James Madison’s Montpelier and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, with Monticello having the most prominent and provocative discussions of slavery. Monticello stood out in part for its efforts to create a dialogue between the history of slavery and contemporary responses to it, for instance displaying Titus Kaphar’s painting, Page 4 of Jefferson’s “Farm Book”, January 1774, Goliath, Hercules, Jupiter, Gill, Fanny, Ned, Sucky, Frankey, Gill, Nell, Bella, Charles, Jenny, Betty, June, Toby, Duna (sic), Cate, Hannah, Rachel, George, Ursula, George, Bagwell, Archy, Frank, Bett, Scilla, ?. This striking painting was displayed front-and-center in one of the first rooms we were ushered into on our guided tour of the house. My 8-year-old son, unabashed, raised his hand and asked why the man’s face and hands were blacked out by tar, offering our guide an opportunity (no doubt by design) to explain the painting as the artist’s response to slavery at Monticello and challenge all of us to consider the contradictions of Jefferson as a person and a historical figure.

While I found it refreshing to encounter someone knowledgeable about the history of the estate who was unafraid to tackle the messiness of Jefferson as a person and an historical figure, Monticello has received criticism for their efforts to “balance the narrative of history.” Some members of the public have complained that featuring the history of slavery and enslaved people at Monticello makes it difficult for visitors to focus on and appreciate the brilliance, innovations, and achievements of Jefferson. (It seems to have entirely escaped them that this blurring of focus is precisely the point of expanding the historical narrative or the fact that his brilliance was in part only possible because of a foundation of slavery!)

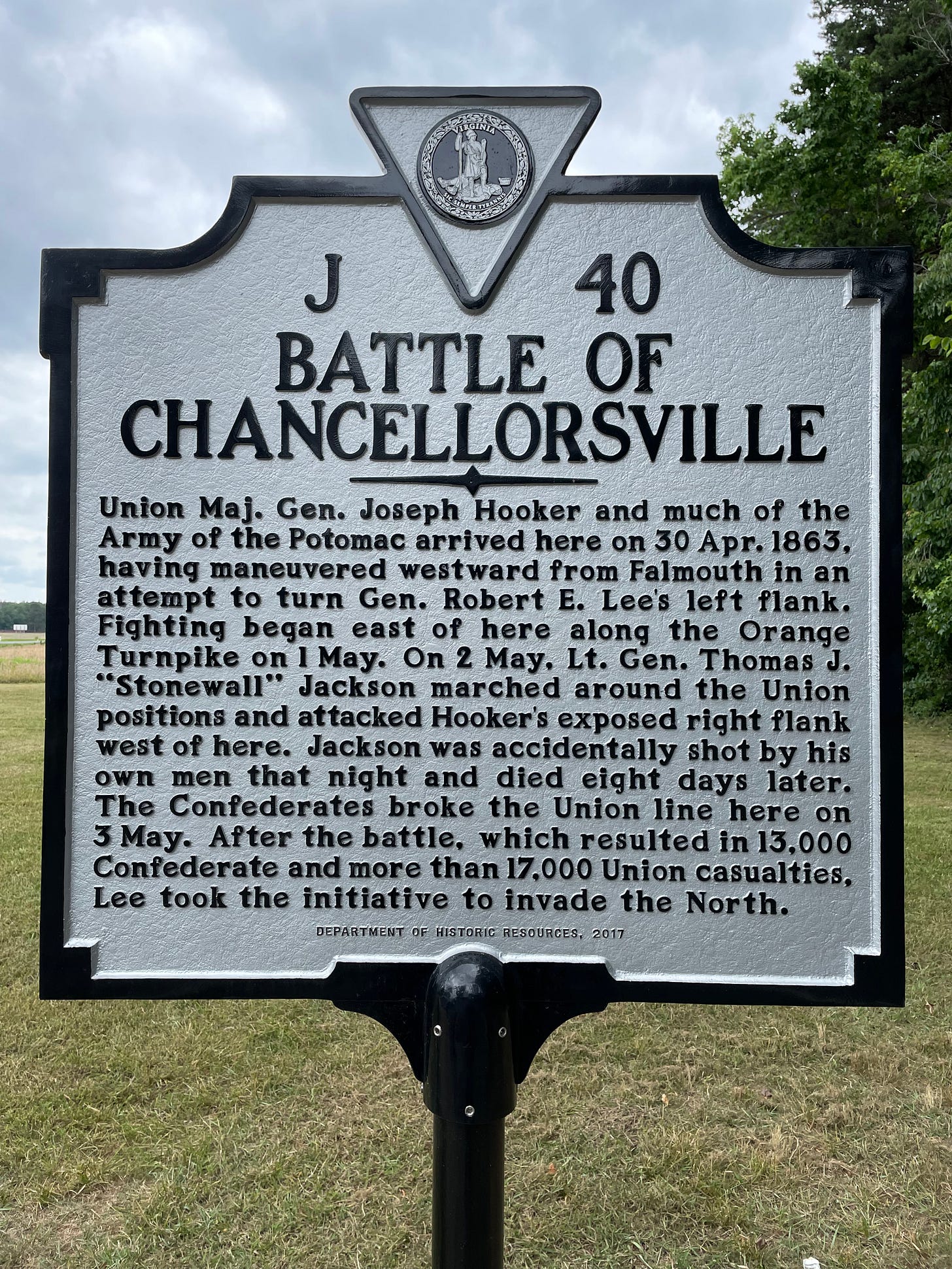

Contrasting our tour of the plantations of former Presidents were stops at Civil War battlefields like Chancellorsville, Appomattox Court House, the American Civil War Museum, and Ford’s Theater: the detritus of war—bullets, pins, thick chunks of cannonballs—packaged and sold after being harvested from nearby battlefields; John Wilkes Booth’s pistol, the weapon that fired a bullet into the brain of Abraham Lincoln, on display for curious eyes; the small parlor of the McLean House, where Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant. As opposed to the romantic, Hollywood-inspired pictures of the Civil War era and the heroic patriotism of the Revolutionary War, our summer tour weaved together in a very physical and visceral manner the ways in which the slavery embedded in America’s origins set the stage for the ultimate devastating moment when it erupted and tore the nation apart. And when we drove into Washington, D.C. the tension and turmoil of all we had seen was cooled in the white marble, bronze, and granite of national monuments honoring victories, ideals, and heroes—a contrast making it all the easier to understand their role in America’s retelling of its own story.

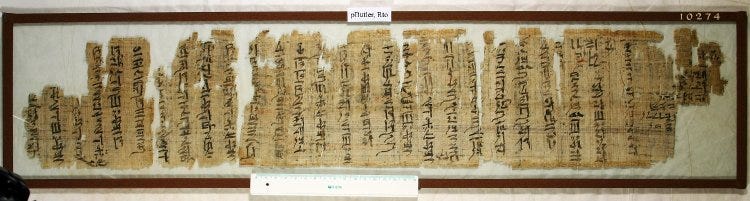

There is a well-known ancient Egyptian text known as The Eloquent Peasant that tells the story of a peasant unfairly accused of theft by a wealthy landowner who imprisons and beats him. The peasant’s eloquence of speech in defending himself impresses and entertains those in power so they draw out his court proceedings, increasing his hopelessness to the point that he considers suicide. Eventually he is elevated through the courts until he stands pleading his case before the king of Egypt. As Kara describes in The Good Kings (p. 37),

It’s a cruel tale of inequality and power, but Egyptological attention has been focused on the elegant turns of phrase and extraordinary aphorisms of the peasant, with little examination of the authoritarianism that put an innocent man into an impossible situation…As for the men in authority, they knew they could ignore the human trauma before their eyes and enjoy the spectacle of beautifully spun prose and brilliantly conveyed wisdom.

As with all great works of literature, there are many levels on which this text can be discussed. Kara uses this text to highlight a modern comparison with police violence against Black Americans. I see Egyptology’s preoccupation with the literary elegance of the text and The Eloquent Peasant’s fictional elites’ enjoyment of the peasant’s beautiful speeches as parallel with our modern preoccupation and enjoyment of “the spectacle of beautifully spun prose” of American history written through our national monuments, memorials, and historical sites. These places can be important tools in helping us understand our shared past and common values, but we should not take in the stories they tell with passive acceptance. If you always find history inspiring and comfortable, examine your sources because you’re doing it wrong.

Part of what I saw this summer tells me that in some ways America is finally beginning to peek over the rose-colored glasses through which we’ve all—on one level or another—been content to view our national history and acknowledge that the past is not past. In this era of misinformation and a growing segment of society that chooses to acknowledge only the history that it likes, we have a greater need than ever for historical sites that engage in a good-faith endeavor to preserve, present, and pass on the knowledge of our messy troubled past, both the ugly and the ideal, so that we may all learn from it. Constructing and memorializing simplified, positivistic narratives of history endangers our future and makes fools of our children. We fail to understand, preserve, and pass on the complexity and contradictions of the past at our peril.