Virtual Exhibitions and Archaeological Reproductions

Misleading and elitist or the best way to preserve our cultural heritage?

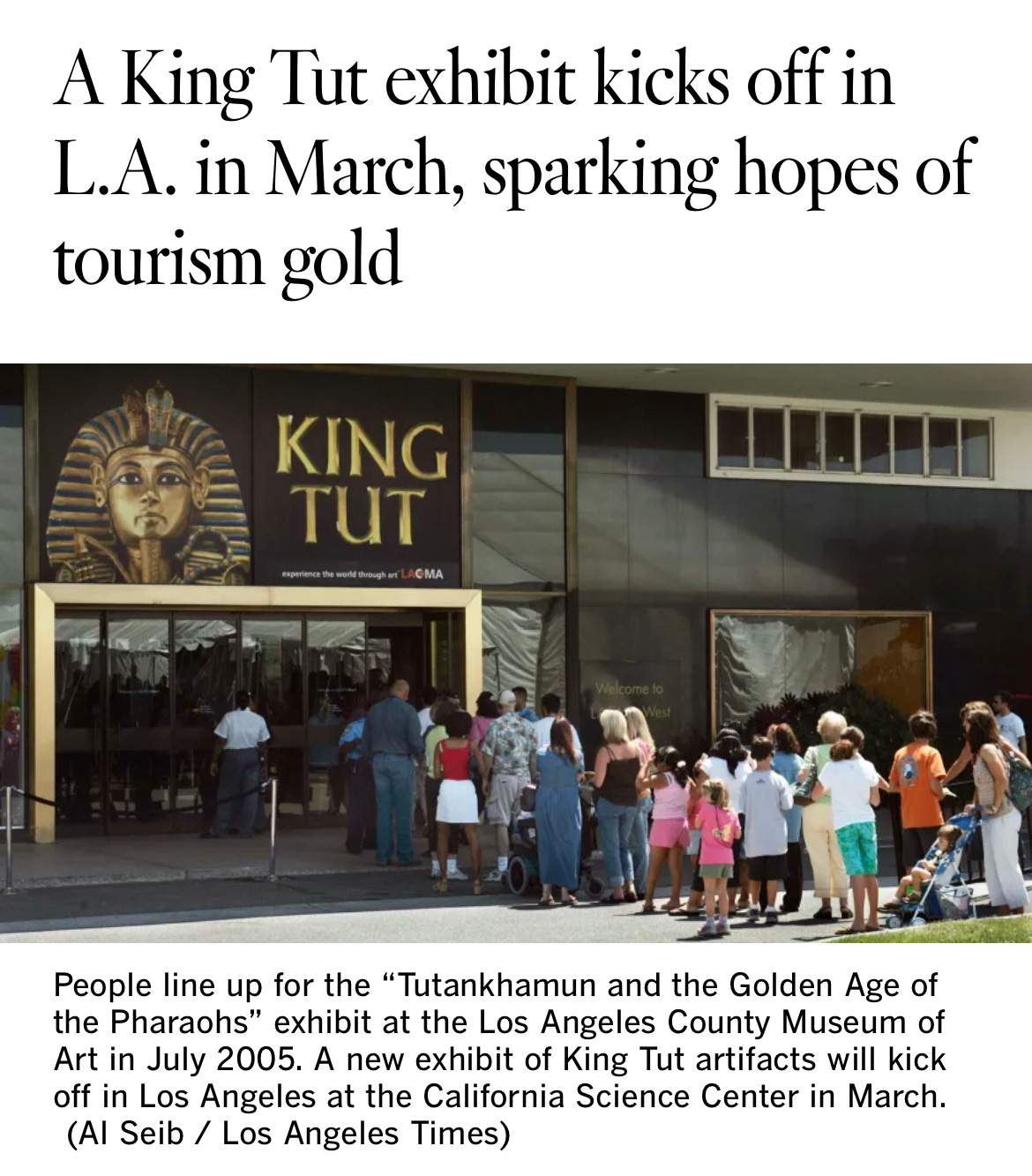

Not long after Kara and Jordan recorded their podcast discussion on environment and geography in ancient Egypt, the ways in which human activity has changed the environment and landscape of Egypt over the millennia, and how that has affected archaeological sites, I came across an ad for National Geographic’s Beyond King Tut: An Immersive Experience. Tutankhamen and the artifacts from his tomb will forever be the subject of iteration after iteration of blockbuster and blockbuster-wannabe exhibitions, but what caught my attention about this one is that it will have no visitors peering into vitrines displaying artifacts in dimly lit galleries. Beyond King Tut is billed on the website as a “cinematic experience immersing you in the world and tomb of the fabled boy king. Travel back over 3,000 years and embark on a journey to Ancient Egypt with soaring never-before-seen visuals. Get your tickets!” Currently showing at The National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C., this virtual exhibition got me thinking about a topic that has always left me feeling conflicted: virtual and/or reproduction exhibitions. That is, should we always prioritize the authentic and real, or can we look to exhibitions, shows, and displays of archaeological artifacts and sites that are centered around virtual experiences or display?

Spending a decade of my career in front of public audiences in classrooms and museum galleries as an educator and communicator of history, I’ve had lots of time to thoughtfully consider this issue. Let’s start with the pros--all of which we should see through the lens of living on a planet now experiencing the consequences of human-induced climate change:

Virtual and reproduction exhibitions protect artifacts and archaeological sites from the damage caused by our consumption, not to mention the foot traffic all over cultural heritage in general. As Kara puts it, just think of your fave hole-in-the-wall authentic restaurant before and after that killer review in the paper everyone reads. It kind of ruins the restaurant, what it used to be. In the same way, artifacts kept out of constant exhibitions are protected from the hazards of transport from their home museum to venues around the globe and archaeological sites that limit their attendance can remain protected from the inevitable damage caused by thousands of tourists flocking to them each year. For example, creating an archaeologically detailed, scaled reproduction of Tutankhamen’s tomb could cut down on the number of annual visitors descending into his actual tomb, where their breathing and sweating in those close quarters can cause damage to the wall paintings—not to mention the mummy still on display in the sepulcher. Such exhibitions also increase access to cultural heritage for those who cannot travel to see the pyramids at Giza or the slopes of Machu Picchu. Many people do not have the time or money or physical ability to travel the world. Virtual and reproduction exhibitions allow people to experience artifacts and archaeological sites that they may otherwise have no opportunity to see in-person. Reducing such recreational travel also helps decrease global tourism’s carbon footprint.

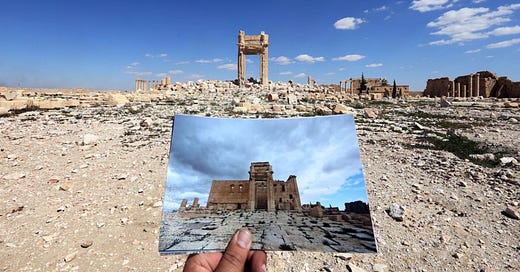

Another potential advantage of virtual and reproduction exhibitions is that a detailed reproduction or virtual record of a site or artifact may become invaluable if anything should happen to the original. Archaeology is inherently destructive. The tomb of Tutankhamen was once stuffed with treasures—now it’s empty. A mock-up of his tomb can reconstruct what Howard Carter saw when he first looked inside that break in the wall. Or consider the damage climate change is already causing to archaeological sites across the world. In Egypt the rising water table and concomitant salinity are causing temple reliefs to crumble and flake. Consider the destruction war has brought to museum collections. Dozens of ancient Egyptian pieces were incinerated in bombing raids during World War II in Europe. Ongoing military conflicts and the resulting social unrest in countries like Syria, Iraq, and Ukraine have decimated museum collections and archaeological sites, causing the permanent losses of cultural heritage that can never be replaced.

It’s worth mentioning that the idea of creating copies to increase access, enjoyment, and ownership of art and architecture is not new. The ancient Roman world was full of Roman copies of lost Greek original sculptures—many of these Greek originals we only know of because of the Roman copies! One of the most famous of these oft-copied Greek sculptures is Praxiteles’ Aphrodite of Knidos (a.k.a. the Knidian Aphrodite). In the 4th century BCE the temple of Aphrodite at Knidos (located in modern-day Turkey) commissioned a sculpture from the famous sculptor Praxiteles. The famed artist produced not only one of the first Greek life-sized depictions of a nude female, but a nude female provocatively reaching for a towel after a bath, her hand lightly hiding her vulva and leaving her breasts fully exposed. To put it mildly, the Greeks were not known for their female nudes. Greek art was dominated by the heroic male nude with his dainty, flaccid penis. So sexy and provocative was this Knidian Aphrodite that the mere sight of the sculpture was said to have excited men sexually and even inspired one young man to attempt to have sex with it, leaving a “stain” on the statue. What was I just saying about reproductions protecting the originals? This legendary incident is an extreme example, but perfectly illustrates the advantages of making reproductions available.

And so, Praxiteles—whom, it should be noted, was possibly influenced by west Asian art that was much more comfortable displaying female nudity—produced an image that reverberated around the Greek world. Tourists flocked to see his original work, and very quickly copies began circulating throughout the Mediterranean world and continued to do so throughout the Roman period and beyond. These copies increased access to a famous work of art that most in the ancient world would likely never have been able to see in-person, easing the flow of eager tourists to the Temple of Aphrodite at Knidos, and no doubt helping prevent additional abuse and damage from masturbating tourists.

Another great advantage of virtual and reproduction exhibitions is that they are likely money-savers for museums and exhibition venues. If an exhibition is pre-packaged, you don’t have to pay curators at every venue, virtual displays and reproductions don’t need conservators to look after them, you need fewer museum preparation staff to design and setup and take down the exhibition space, and let’s not forget the savings on insurance costs for artifacts(!). These pre-packaged exhibitions usually come with pre-produced videos, which is cheaper for the museum, sure, but it also provides a reason not to hire experts and educators to guide the public through the galleries. In general these kinds of exhibitions also require fewer administrators to draw up loan contracts and terms for artifacts or artworks coming to a museum as part of a special exhibition. There are probably lots more knock-on budget friendly effects for museums and venues that I’m not thinking of, but suffice it to say that it is easy to see the appeal of these types of exhibitions from the perspective of museums and exhibition venues that often operate on limited budgets and rely on drawing visitors through their doors to help bolster operating costs.

These all sound like excellent benefits that have the potential to increase access to cultural heritage and even protect artifacts and archaeological sites that can never be replaced. But as with so many things, it’s more complicated than that. One of the first lessons I learned as a museum educator as I interacted with both children and adults in the galleries of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) is that a lot of people—especially those from places where access to museums is limited—have a hard time believing that museums hold collections of “real” art and artifacts. The most common question I got at both LACMA and the Getty Villa, particularly from school groups, was “Is it real?” Knowing this is already a point of confusion for some visitors, I worry that virtual or reproduction exhibitions might encourage the misunderstanding that museums are full of replicas or “fakes.” For me this is a significant ethical con because it is important for experts and educators to have the trust of the public and be seen as trusted sources. In recent years we have seen the damage done when experts are distrusted and disregarded and dismissed as purveyors of “fake news” or false information.

Unless such exhibitions state outright and unambiguously that they offer virtual experiences or display reproductions, it can be confusing for the public and some might feel misled. One aspect of the Beyond Tutankhamun exhibition website that I noticed immediately is that it is not crystal clear on the landing page that there are no artifacts in the exhibition, but the iconic image of Tutankhamun’s mask appears nearly full screen. No doubt this ambiguity exists in the hope of ticket sales to those who might not click around and find more details and excitedly but mistakenly buy tickets thinking they will see artifacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb. They might think twice before buying tickets to the exhibition if it was clearly stated there will be no artifacts displayed. You may think I’m taking a cynical view, but I have witnessed exhibition sponsors and creators do this before.

In 2005 when LACMA hosted the Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs exhibition, I took many public and private groups through the galleries, and one of the most common complaints I received was from people who thought that the small canopic coffin plastered all over the exhibition promotion materials from handheld brochures to massive banners on the sides of buildings was actually of a full-sized coffin or mask and that it would be on display in the exhibition. Visitors wandered throughout the whole of the exhibition and finally at the end asked me where it was, at which point I would explain that the image was a detail from the small canopic coffinette—a miniature coffin meant for a mummified organ, not a full-sized coffin made for the deceased king. I and other museum staff members did our best to soothe the ruffled feathers of visitors who felt they had been misled and brought this issue up with the exhibition sponsor staff members, but no one promoting the exhibition took any steps to make clear to ticket buyers that, by the way, there was no mask or full-sized coffin of Tutankhamun on display.

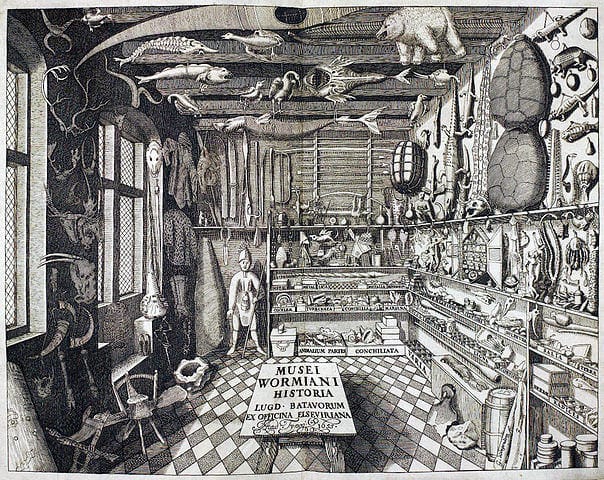

It might also be argued that virtual and reproduction exhibitions are elitist. I will be the first to admit that museums and art galleries themselves are inherently elitist, right down to their roots in the “secret” cabinets and private collections of European aristocrats of the 18th century CE. However, two seemingly contradictory truths may simultaneously exist: Museums increase public access to cultural heritage, and they are elitist. Similarly, virtual and reproduction exhibitions can increase public access to cultural heritage and may still be elitist. Those with money and social and political connections will always have access to the “real thing.” Limiting access to ancient artifacts, art, and archaeological sites, can easily become even more incentivized than it already is because museums and archaeological projects are always in need of funding. In the current political and financial climate, funds for cultural institutions are becoming even more scarce.

Thinking in broader economic terms, these kinds of exhibitions can have economic consequences far beyond the exhibition walls. If tourists feel like they don’t need to travel to see famous museum collections, artworks, or archaeological sites, the loss of tourist dollars in those places can have economic consequences—from museum professionals to restaurant and hospitality workers to those who work at archaeological sites or have jobs otherwise connected to a tourist economy, business or the ability to work in those jobs could be lost altogether. Looking only at museums, I mentioned earlier that fewer museum professionals are needed to support virtual or reproduction exhibitions. Jobs for museum professionals are already limited. I myself have experienced a layoff at one of the richest museums in the world. No matter how history is presented to the public, we need people who understand how to maintain and protect cultural heritage and how to present it to people in a coherent and compelling way. Virtual exhibitions are another point of pressure that may ultimately contribute to the further contraction of the museum field—a field, by the way, largely dominated by women.

Women are often the keepers of stories and traditions, so it is no surprise that they can be drawn to museum careers. This brings me to my final con of virtual and reproduction exhibitions: imagination and experience. My first experience in a museum was in the ancient Egyptian galleries of Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History. The mind-blowing magic of seeing with my own eyes an object made, possessed, and used by human hands millennia before is something I wish everyone could experience. The opportunity to enter an ancient temple or tomb or walk the paths of a great city of a lost civilization offers the imagination a perspective that can be gained no other way. These experiences should not be set aside lightly or dismissed in the current fervor for virtual experiences. My years in museums have proven to me that sometimes the best way to help someone connect with history is to stand with them face-to-face and share knowledge. Institutions responsible for maintaining cultural heritage sites, museums, and exhibition venues should commit to providing expert communicators at sites and within exhibition spaces to promote understanding and engagement by members of the public. These programs are where we plant the seeds for the investment we hope future generations will make in continuing to preserve our cultural heritage sites and artifacts in perpetuity.

There are surely several benefits and consequences I have not mentioned here, including those that might be unforeseen. It is likely that as virtual and reproduction exhibitions grow in popularity there will be both positive and negative effects that even the community of museum and cultural heritage professionals have not anticipated. This is especially true as the ramifications of climate change begin to be fully realized. We can only do our best to make decisions that walk the line between the need to preserve the world’s cultural heritage while also facilitating public access to it and meaningful understanding of it. Each of these elements is imperative, because if humanity ever fails to experience and find meaningful understanding in cultural heritage our will to preserve it for future generations will also fail.