The “Younger Memnon”: A Lesson in Power, Reuse, and Colonial Trophy Hunting

Ask whose story is being told—and whose is being erased

The “Younger Memnon”: A Colossal Lesson in Power, Reuse, and Colonial Trophy Hunting

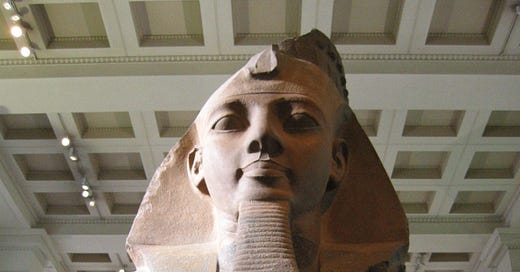

Walk into the British Museum, turn left to the Egyptian art galleries, and you’ll meet him. Nine feet tall, weighing over seven tons, with a stony, inscrutable smile and a nemes headdress placed on a king’s head, just so. This is the “Younger Memnon”—the head and chest of a colossal statue originally carved for one pharaoh, reused by another, and now standing in London as a monument not just to ancient Egypt, but to centuries of British colonial obsession, imperial posturing, and the quiet power of artistic reuse.

Let me be clear: this is not just a statue. It is a masterclass in the ideologies of power, a flex of dynastic egos, and—yes—even a war crime in granite.

Let’s start at the beginning. As Amber and I discussed on Afterlives of Ancient Egypt Episode #114, “The ‘Younger Memnon’: A Colossal Case of Ancient Reuse and Modern Empire,” this statue was made for Amenhotep III, one of Egypt’s great builder-kings of the 18th Dynasty. His reign was long, wealthy, and, if the archaeology tells us anything, deeply performative in the ideologies of divine kingship. He wasn’t subtle. When Amenhotep wanted to show his solar connections, he didn’t just write a hymn—he carved a twenty-foot-tall likeness of himself in a two-toned block of granite, the head red like the setting sun, the body dark like the fertile earth or the god Osiris. He made himself the sun, rising and setting with cosmic predictability. No press releases needed. Just stone.

Then after the long years of crisis brought on by Akhenaten’s religious experimentation whose own over-the-top performances of divine kingship toppled his dynasty, came Ramses II, the 19th Dynasty’s PR machine. This guy was a third-gen military man, and he wanted statues everywhere. No time for bespoke commissions that speak to the high elite when there are temples to fill and a populace to impress. So what does Ramses do? He grabs what’s lying around—including statues of Amenhotep III—and repurposes them with his own face, his own name, his own idealized chest.

This is where things get really interesting.

Because if you look closely at the “Younger Memnon”—and please do, the British Museum has gloriously zoomable images—you can see the makeover. The eyes were reshaped, the brows shaved down, the lips retouched, the man-boobs (think prosperity! Disposable income! The rarity of age!) flattened and upgraded to strong pectoral muscles. Amenhotep’s regal, kohl-lined gaze? Gone. Ramses wanted a soldier, not a sun god with eye makeup. He also wanted frivolity and celebration. He drilled some smile lines into the corners of the mouth and called it a day. Ramses—or at least his agents who had been ordered to do that reshaping—didn’t care if the nose didn’t match his naturalistic portraiture. This was propaganda. He needed statues fast, and Amenhotep’s leftovers would do just fine. In fact, one could argue that the 18th Dynasty’s excesses demanded the visible reuse of precisely this king’s monumental work because it pleased a populace distrustful of that kind of kingship.

But wait, there’s more.

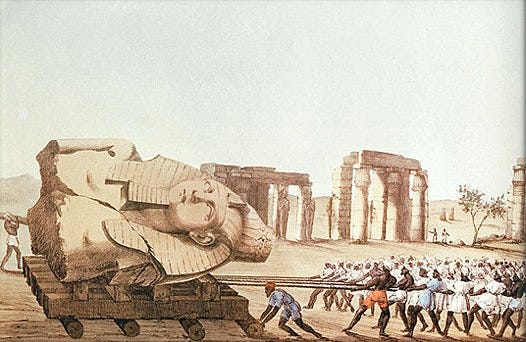

Flash forward to the 19th century. Enter Giovanni Belzoni, former circus strongman turned traveler and antiquities wrangler. He, along with other agents of empire, eyed the fallen statues at the Ramesseum—the temple of millions of years of Ramses II—and saw not a sacred relic, not a piece of Egyptian heritage, but a prize for those powerful enough to take it. The French had already tried to engineer the colossal statue’s removal. They failed. The British, determined not to lose out to Napoleon’s floundering ambitions, got the job done. They hauled the fractured head up the Nile, across the Mediterranean, and back to London in what was essentially the ancient equivalent of a moonshot.

All this—years of work, thousands of pounds, a spectacle of engineering—for a decapitated statue with no arms.

Why?

Because it wasn’t about Egypt. It wasn’t even about the statue. It was about power. It’s always about power. The British Museum didn’t tuck the Younger Memnon into a back corner. They planted it right at the entrance to their Egyptian galleries. “Look what we can take,” the placement says. “Look how strong we are.” Like planting a flag on the moon, but with the giant head of a millennia-dead king from the northeast corner of Africa.

And let’s not forget Percy Shelley, whose 1818 poem Ozymandias was inspired by this very head—or perhaps its twin still on site at the Ramesseum. “Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair.” He meant to mock the hubris of ancient kings. But isn’t there something ironic about that same line being quoted by the imperialists who stole the statue in the first place? Who later lost their vast empire?

Fast-forward again. Today, when you visit the British Museum’s website, you’ll find that the statue is labeled as “Ramses II.” No mention of Amenhotep III. No acknowledgment that this was a reused piece, a palimpsest of royal identity. Just a tidy label. 19th Dynasty. Ramses the Great. Move along.

This is an interesting omission, one that reminds us that museums are political spaces. They are not neutral. They do not exist outside of time. When they refuse to tell the full story of an object—its multiple lives, its re-inscription—they’re participating in a system that upholds the narratives of power, that objects somehow gravitate to particular places, that these museums are better caretakers, that such magnificent pieces would be unsafe in their homeland. More specifically, by ignoring the reuse of the statue by Ramses II, the British Museum can ignore its colonial extraction. Why tell you about Ramses taking the colossal from Amenhotep when that will just remind you that Britain took it from Egypt. Why even discuss how Amenhotep III sourced the stone in Nubia and brought it to Thebes, because that adds another colonial dimension to the piece.

Now, don’t get me wrong. I love museums. I’ve worked in them. I’ve taught in them. But I also know how they work. And I know who they were built for. The labels are written for simplicity and audience understanding, yes, but labels are also indicators of power and ownership. Museum boards and administrators determine what information gets highlighted. The truth—complex, messy, and often inconvenient—gets cut in the same way that Amenhotep’s eyes were recarved. The result is a more palatable story for the current owners, certainly one that flatters modern power just as much as it is tied to the antiquity of divine kingship.

The truth is, the Younger Memnon is not just a statue. It’s a challenge. It asks us to look deeper, to peel back the layers, to see not just Ramses but the ghost of Amenhotep III beneath, and the specter of Nubian exploitation underneath that. To recognize not just the artistry, but the theft. Not just the face, but the systems of control that have kept it—literally and figuratively—in place.

And maybe, just maybe, it asks us to stop pretending that we’re different from those ancient kings. Because we still love a good old trophy. We still crave the display. And we still tell ourselves stories to justify it all.

So next time you see the Younger Memnon, whether in person or on a screen, don’t just look at the surface.

Look on its works, ye reader, and think again.

Conversations with Kara: Absolute Power and it's Legacy

In this special episode of Science Factory, host Alicia Flores and Kara dive into the complexities of power, gender, and economy in ancient Egypt, exploring themes from Kara’s most recent books, including Recycling for Death, Ancient Egyptian Society, and Coffin Commerce.

Thank you for a beautifully written and thought provoking piece. The US is also filled with wonderful beaux art museums filled with stolen loot. I share the guilt: I love to go to them, and if we gave it all back, most of it I would never see.

Reusing ancient statuary and construction makes sense given the difficulty and cost of their construction in the ancient world. One wonders how much reusing monuments was a cover for touted prosperity...or a contributing factor to what actual prosperity occurred after the savings.

Adding one's own touches to a monument of another's glory also fits in with Egyptian liturgical practice, which saw ancient hymns and texts combined and developed in novel ways over the centuries, even swapping out one deity or Pharaoh for another as a text was reused and copied to another temple. The story told then becomes not just the person or liturgy of the past, or the present, but of both. For Pharaohs the legitimacy gained through a lineage seemed more common than trying to blot out a prior rival.