Materializing Light

Some Musings after Kara and Amber visited the Lumen Show at the Getty Center

Human perception of the universe begins with light. Our understanding of light is so fundamental to the way in which we perceive our physical world, pursue knowledge, and contemplate our own existence that for millennia we have sought to harness it, discern its properties, and use it to commune with the divine. On Afterlives of Ancient Egypt (Episode #109, “Solarism and the Great Hymn to the Aten”), we recently talked about solarism in ancient Egyptian religion and how it coincided with the rise of divine kingship, how the earliest monumental architecture on earth was built to honor light and solar divinity and act in alignment with celestial bodies. The theological universalism of Egypt’s late New Kingdom emerged from the contemplation of the divine centered on the sun and its light—and the Egyptologist must remind herself that these are natural phenomena experienced by all of humanity (!!), that other cultures drew the solar orb and the rays emanating from its center, that other peoples connected golden light with kingly rule. Indeed, the comparisons can be uncanny—or maybe not strange at all, given we all occupy the same earthly plane.

Last year the Getty Center in Los Angeles hosted a special exhibition, Lumen: The Art and Science of Light, which beautifully explored this universal human experience with light. The exhibition looked at how medieval (800-1600 CE) artists, theologians, astrologers, and philosophers across Europe and the Mediterranean world sought to understand light, and walked visitors through the ancient and premodern scientific foundations of Islamic and Christian knowledge of the sky, their understanding of vision and light, and how light was used to enhance the spiritual experience of divinity within sacred spaces. The questions being asked were: Is God light? Are we beings of light? Are we god? Is light time? What is time? All the big theological issues were under the microscope, as it were.

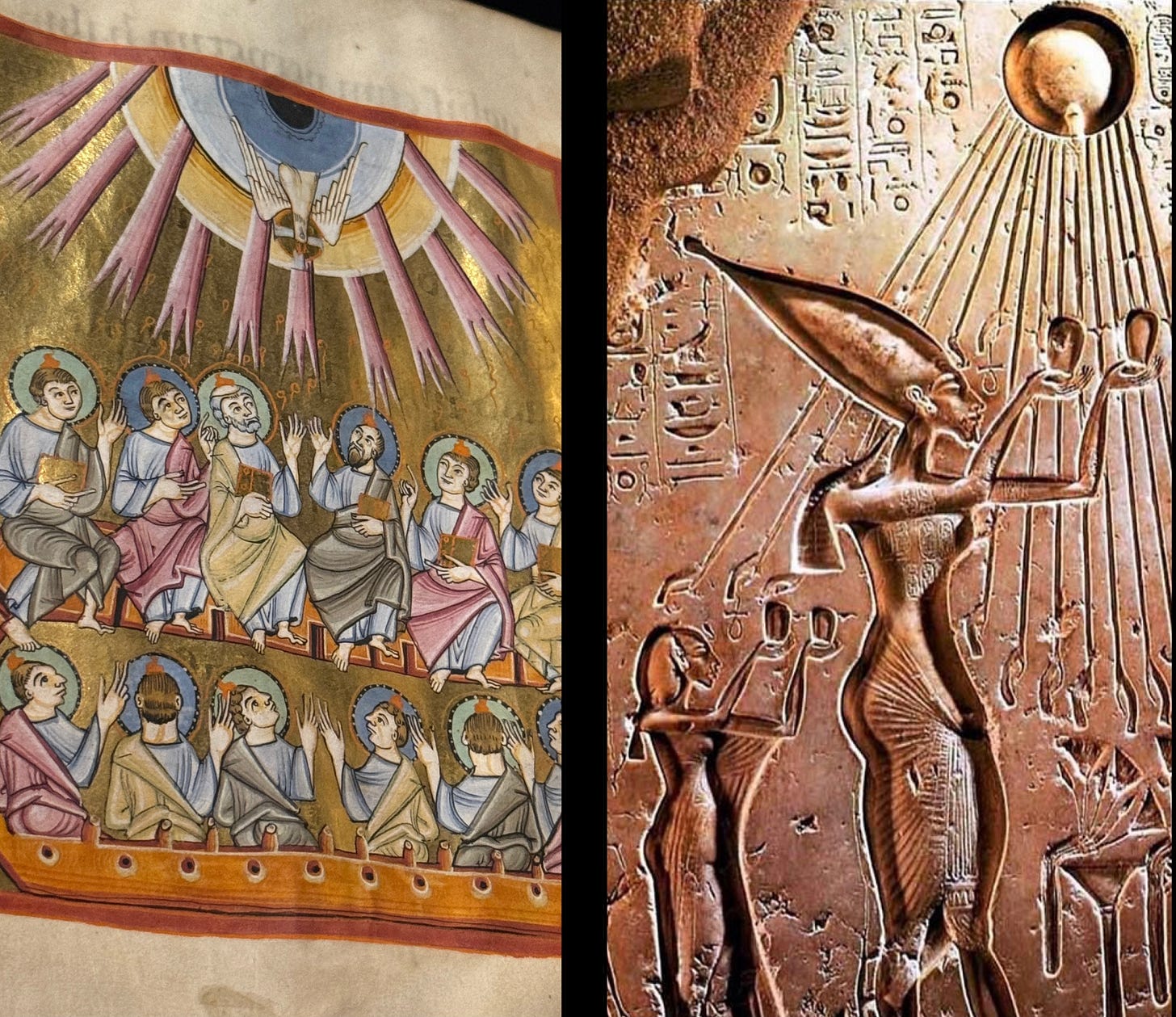

To the Egyptologist, the ancient roots of the medieval world’s understanding of light and the belief in its divine origins were present in every artifact and artwork of the exhibition, and observations on ancient Egyptian parallels leapt out everywhere. Common threads, like the medieval belief that knowledge of the natural world and the divine can be conducted and communicated to worshipers via light, are evocative of ancient Egypt’s solar cult, especially the Atenism of Akhenaten. The visual parallel with ancient Egyptian depictions of the Aten’s rays beaming down on Akhenaten with outstretched hands offering the ankh (symbol of life) and a 9th century CE illuminated manuscript of the Pentecost in which the Holy Spirit’s rays of light extend down from the heavens carrying divine knowledge and igniting tongues of flame on the heads of worshipers is irresistible. Medieval and contemporary artists’ efforts to capture the immaterial (in this case, light) in the material is also something they have in common with the ancient Egyptians. Among the contemporary works included in the exhibition, E. V. Day’s dramatic Golden Rays/In Vitro (2018), with its three-dimensional formation of illuminated rays descending from one precise point via fiber optic cable and gilded aircraft cable, brings to mind the straight sides of ancient Egyptian pyramids which, as Kara reminds us on the podcast, were intended to represent the sun’s rays in stone. Like the illumination of the Pentecost, Day’s work also calls back to the image of the Aten, allowing one to better understand it and see it for what it is—a three-dimensional representation of rays of light extending down from the sphere of the sun rendered through the two-dimensional ancient Egyptian artistic canon. Standing there in that space, with the light beams joining heaven and earth, granted some small idea of what Akhenaten was trying to do with his new theology.

Ancient, medieval, and contemporary artists and architects have all explored light and how it interacts with various media, surfaces, and materials, and one of the strengths of the exhibition was the way in which the curators Kristen Collins and Nancy Turner leaned into the opportunity to use the very subject of the exhibition—light—to draw the visitor out of passive observation into a more active experience, using light in the gallery space to create creative spaces demanding we think about how light shapes the experience of worship. From the carefully chosen precious metals and stones in medieval altar pieces, reliquaries, and architectural elements to the contemporary artworks woven throughout the exhibition, it was a nice touch and an ever-present reminder that light can be used to create a visceral, physical experience as well as an intellectual or spiritual one.

Our fascination with light persists—there is still much about light and its properties that science has yet to fully explain (just ask a quantum physicist!), including an understanding of its absence. The final gallery featured a work by contemporary artist Anish Kapoor called “Non-Object Black, 2018,” in which he used one of the darkest pigments ever created. Known as vantablack, it absorbs 99.965% of visible light. This pigment reflects so little light that the viewer has difficulty seeing depth and texture. Looking head-on, one sees only a flat diamond shape, but moving around the object and looking from different angles reveals a three-dimensional form. (Watch this short video to get an idea of how Karpoor’s Non-Object Black series messes with the viewer’s perception.) The absence of light can be as striking as its presence, and Kapoor uses the simple diamond shape and an understanding of physics to fool with the viewer’s perception and visual experience. It is at once a two-dimensional and three-dimensional artwork, and it scrambles the brain’s circuits a little: We realize how easily our senses are fooled and that our ability to perceive the universe is limited. We wonder what lies beyond our perception and how our own senses might be deceiving us.

Black hole, anyone?

Light is a natural element that we tend to think of as an unbiased means of perceiving the world around us, but for thousands of years, from the pyramids of Giza to contemporary art galleries, it has been used it to shape our aesthetic experiences of art, culture, and religion in decidedly biased ways. We have always agreed on the presence of the light. The question has always been what we see in it.

The Lumen exhibition is long closed, alas, but you can visit the exhibition webpages and still buy the excellent catalogue. And you can go touch grass, bathe in some sunlight and merge with the divine. But not too much. It might burn you…

Listening to your other recent episodes on the Aten/Akhenaten (same thing?) you made a comment about what's commonly referred to as the 'sun disc' actually being a globe. Beyond the obvious that most hieroglyphs are 2D representations of 3D items, surely this relief (and others, I assume) shows a depth to the Aten (and the rest of the Trinity) that tries to capture that extra dimension as far as the medium allows. After all, if the Aten was truly meant to be flat, why portray it as otherwise, when to show it raysed would be more complicated and time-consuming? (No apologies for the pun.)

Even before seeing this, I also made an intuitive leap, which while maybe unsupported by any direct evidence, at least has a reasoned logic to it. Thinking about Khepri, who helps the sun to move, what would that look like in the physical world? To quote Wikipedia: "This mirrors the manner in which a scarab beetle pushes large *balls* of dung along the ground" (my emphasis). Aside from point A above, surely the Ancient Egyptians who would've been intimately aware of this process as a part of daily life, would automatically think of it when seeing depictions of Khepri and, by extension, any image of the sun. It's just unfortunate that there aren't any around to ask.

Love your article. And it is a great topic, I think your questions and focus on this topic were spot on. Thanks for sharing