This post is a companion post to this week’s podcast episode “Labor Relations in ancient Egypt.” Listen now wherever you get your podcasts, or here on Substack:

We see the emails everyday—50% off Sale, Clearance!!, Get it before it's gone! Clothing stores are constantly bombarding us with emails, advertisements, and offers to entice us to buy, buy, buy, to engage with never-ending consumerism. We know we don’t need any more clothes, but “oh that sweater is soo cute” and “Everything I own is sooo last season.” The societal pressures to keep your fashions up-to-date and to represent your ever-changing identities through your dress require all of us to engage with the fashion industry. And most of us have to do it on the cheap in this late Capitalist world. Oscar de la Renta and Chanel are beyond our budgets. So are most boutiques. The rest of us are left with stores like Shein, Old Navy, Forever 21 and resale stores like Marshalls and TJMaxx to get the latest (or last year’s) styles.

Many of us are aware of the detriments of so-called “fast fashion” and the evils lurking behind the textile industry. Where do I even begin? A quick google search elicits thousands of articles and news stories covering the topic:

The Not-So-Hidden Ethical Cost Of Fast Fashion: Sneaky Sweatshops In Our Own Backyard

Shein Is the World’s Most Popular Fashion Brand—at a Huge Cost to Us All

Even in my city of Los Angeles we document garment workers pressed into “modern-day slavery” being paid cents on the dollar per hour, working in hazardous workplaces. Just two months prior to the writing of this post there was a large fire in the Los Angeles garment district.

But fast fashion is the only option for many of us, if we want to keep our social place, that is. Many of us cannot afford other options, even knowing the environmental and ethical issues behind the industry. (Thrifting is a great option! Check out the Rise of Thrifttok). Many of the more sustainable, small-business based options are too bougie and do not include us in their designs as they are not size inclusive (Fast Fashion Is Bad For The Environment. For Many Plus-Size Shoppers, It’s The Only Option).

In no way am I here to solve the Fast Fashion issue or make you feel repugnant for engaging in fast fashion—I do it too! On a graduate school budget I am not buying bespoke, sustainable, American-made pieces. I shop those Old Navy and Target sales just like everyone else. But my academic side got me thinking… And I am working on a dissertation about fashion in ancient Egypt. So how can we apply these economic issues to the ancient world? Who was producing textiles? What institutions were profiting? I can only speak to New Kingdom Egypt, and of course, the Egyptian textile industry was very different from ours—it was not a global market, capitalism did not have its claws sunk into it yet, and many people engaged in home production of textiles—but that is not to say that people from marginalized backgrounds did not get abused by a system for the advantage of the state, the industry, and the elites. We just can’t easily document it from thousands of years later.

The ancient Egyptian Textile Industry

So how does the ancient Egyptian textile industry compare to our own? What, if anything, can we learn from it?

Textiles were produced by marginalized labor

Ancient evidence tells us that women, immigrants, foreigners, and war captives were major textile producers under the auspices of both the palace and temple industries. Sounds pretty exploitative… For example, Thutmose III records the bringing of captive weavers from both the Levant and Nubia in his Annals from Karnak:

… on the first of the victories which he [Thutmose III] gave me, to fill his work-house, to be weavers to make for him royal, fine linen, white linen, srw-linen, and thick cloth…

Tally of the male and female Asiatics (sic) and male and female Nubians whom My Majesty gave to my father Amun, beginning in year 23 and down to when this inscription was put upon this temple: 1, 588

This statement about where labor for the production of textiles was sourced is corroborated in the tomb of Thutmose III’s vizier Rekhmire, where it is stated:

Rekhmire inspecting the workshop in Karnak and the weavers whom His Majesty (Thutmose III) had brought away from his victories in the southern and northern lands as the pick of the booty, he, the good god, the lord of Egypt, Menkheperre—life, prosperity, health—for the manufacture of king’s linen, bleached linen, fine linen…linen, close-woven linen…

This is but one example of foreign captives from the king’s campaign being brought back to Egypt and “given” to a temple to engage in textile labor. Many of these captives would have been women and children. Children in the ancient world, much like the recent past (think Victorian children in textile mills), were prized for their small size and nimble hands—perfect for textile work.

Not all textile workers were captives or of a lower-status, however. In ancient Egypt, much of the textile work was also being done by women (a marginalized group in their own right) in the various “harem”-palaces scattered around the country. These women were of an elite status and probably engaged in specialized textile work. We know that foreign brides of the king came with large retinues to Egypt, and all of the women among them probably engaged in weaving.

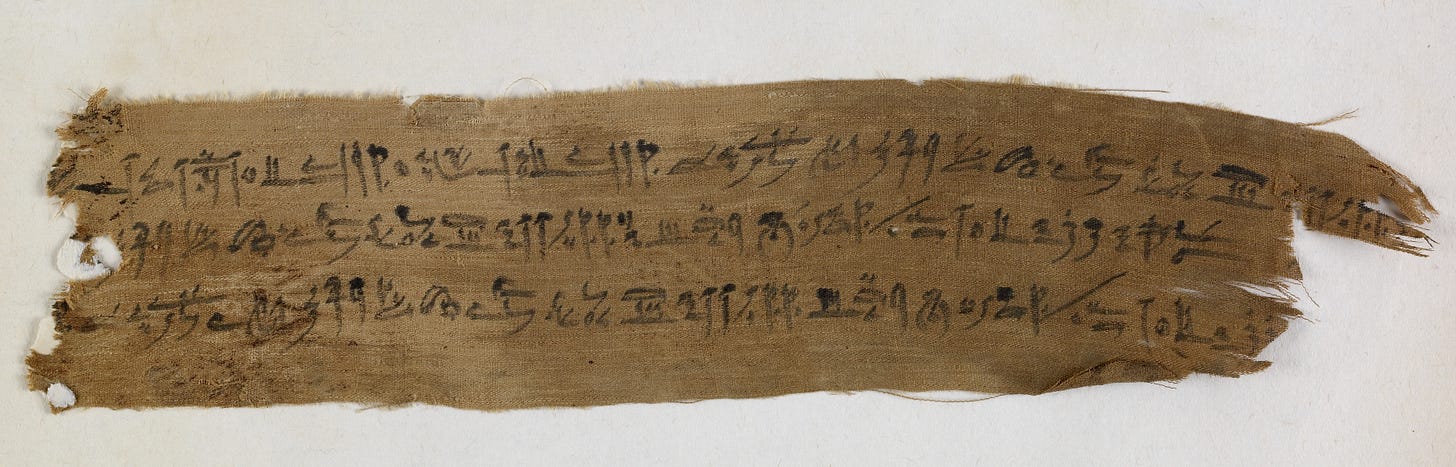

It’s like they brought their own couture seamstresses with them; a queen has got to look good after all (or make money trying). Gilukhepa, the daughter of the Mitannian king Shuttarna II, married Amenhotep III and brought 317 women of her private household with her. It is likely that many of those women were weavers. Maathorneferure, a foreign wife of Ramses III, is known to have been engaged in the textile industry—a papyrus records the sending of a variety of garments under her auspices:

“the king’s wife Maathorneferure (l.p.h) […] [///] ḏꜣy.t garment of 28 cubits, 4 palms, 4 cubits [///] of 14 cubits, 2 palms, breath 4 cubits [///] royal linen i̓dg garment, royal linen mss garment, royal linen, sḏw cloth of first quality…”

Similarly, in the modern world the identities of textile manufacturers and producers span the gamut of social rank—there is foreign, captive, “sweatshop” labor but fine luxury textiles— like the bespoke designer fashions of Paris and Milan— are made by a few specialized elite producers for consumption of the elite minority in society who can afford them.

$$$

In ancient Egypt textiles were a major money producing commodity controlled by the palace and temple industries. Both institutions controlled large swaths of land upon which flax, a water intensive crop, was grown and harvested by their laborers. Unlike our contemporary notions of fast fashion bargains and inexpensive textiles, clothing in ancient Egypt was a relatively expensive good. And finely made textiles were simply unaffordable for everyone but the very rich.

Using inscriptional evidence from Deir el-Medina we can compare the price of different garments to other commodities, such as livestock. For example, a donkey ranged from 25-40 deben, while a cow was 20-50, and a bull was 100-120. Garments ranged in price, dependent on the garment’s size, quality, and skill required to produce it. A standard tunic was around 5 deben, while a cloak could run 20-25 deben, a price comparable to that of a small donkey or cow. Admittedly, price comparisons are difficult in a time and place without standardized “money," but at the very least we can see that textiles were not “cheap” like they can be today. A donkey could change a household’s fortune; this was an indispensable animal, and its cost equated to an ancient Egyptian winter coat (See Jac Janssen’s Commodity Prices from the Ramessid Period (1975) for more information on the price of goods in ancient Egypt).

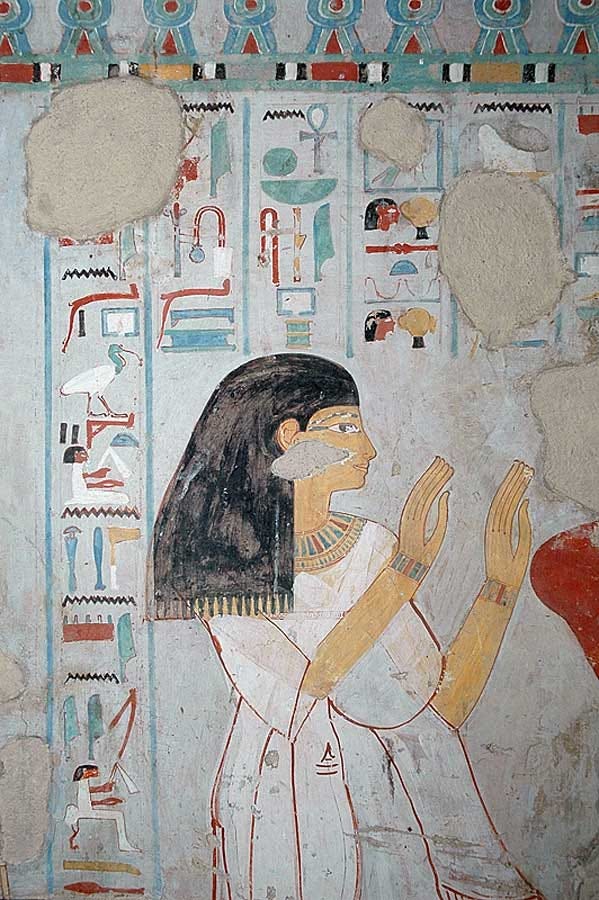

In addition to the institutions that profited from the textile industry, ancient Egyptian elites held textile-related titles linking them to the industry, indicating that they too could partake in the wealth it generated. My favorite example is from Theban Tomb 45. The tomb was originally constructed in the 18th dynasty for a man named Djehuty who was the “Overseer of the Weavers of Amun,” presumably at the Temple of Amun at Karnak. This position allowed him gain wealth and privilege and become one of the select few who had a tomb on the West bank of Thebes—the resting place of the super elites. Later in the 19th dynasty, his tomb was reused by another textile overseer, Djehutymehab. He too oversaw the weavers of Amun. Djehutyemhab also states that his father, Wennefer, was the “Overseer of the Weavers of the House of Amun.” The distinction between “Amun” and the “House of Amun” is unclear, but such titles are known to be hereditary, so it is possible that both titles belong to the same or a similar position.

Why Djehutyemhab reused Djehuty’s tomb is unclear. They were generations apart, but perhaps they were related and perhaps the textiles-related titles were passed down through the family. One would assume Djehutyemhab would have mentioned the relation, if so. Interestingly, when the tomb was reused Djehutyemhab left large parts of the tomb untouched, but he carefully updated the clothing depicted in the painted reliefs to reflect the 19th dynasty styles—can’t have old fashions in your new tomb!

Textiles were massive statues markers, and as such, they were also gifted and exchanged between the great kings of western Asia and Egypt in huge numbers. The Amarna Letters, which document correspondence between ancient Egyptian kings and other rulers, record the gift exchange of textiles both to and from Egypt. Of particular interest is the large number of “exotic” pieces being gifted to the Egyptian king. One letter inventories gifts from Tushratta, the king of Mitanni. Within the huge list of products there are many textiles:

Textiles were major $$$ in ancient Egypt, much like today—textiles make up a current global market size valued near 1.7 billion USD in 2022.

Textiles were reused and repurposed

Nothing went to waste in the ancient world. For those of you familiar with Kara’s work on ancient Egyptian coffin reuse, it may not come as a surprise to you that textiles were also reused and repurposed. We have both textual and archaeological examples of this reuse. Many textiles preserved to us display mends and repairs in the fabric. Bandages for mummification were most certainly repurposed linen. Rags and even ropes could also be made from repurposed clothing.

Texts also record the acquisition of textiles for reuse given their inherent value:

“You shall have some textile and loose rags brought to me.. and they shall be made into bandages for wrapping men” (LRL 20).

Another letter records similarly:

"Send some of the clothes that have been found. It is after I have departed that you shall send them after me," so said he, our lord….He said to you, 'Come after me.' "We handed over the clothes to our mistress….“Open a tomb among the foremost tombs [King’s tombs], and preserve its seal until I shall come, so he said, our lord [i.e. Piankh]. We are obeying orders. We shall see to it that you find it in place” (LRL 28).

Both of these letters date to the end of the Ramesside Period or early Third Intermediate period when there was great unrest—and great reuse—in Thebes. As royal tombs were being looted, textiles proved to be one of the items that was both highly fungible and easily commodified. Someone in the marketplace might wonder where you got all that gold, but would they wonder where you got the cut up linen bandages?

Textile Workers Then and Today

Perhaps it is unsurprising that the ancient Egyptian textile industry, much like our own, was built on the back of marginalized groups—immigrants, foreigners, captives, and women. Much of the textiles produced today are also made by the marginalized people. It is to the benefit of large industries to exploit groups of people who have little power, and the repercussions are minor.

But what about worker’s rights in ancient Egypt? Were there any? We have little evidence for workers rights and workplace disputes concerning textiles workers. A glimpse of the unrest of laborers can be gleaned from one of the Tomb Robbery Papyri (P.BM 10053) that records the thieves who plundered the kings’ tombs—because many of them were weavers of the Temple of Amun!!

On the other hand, we have the famous Strike Papyri that recount “history’s first labor strike” by the workpeople of Deir el-Medina, those who were responsible for building and decorating the kings’ tombs. Kara and I recently talked about labor disputes in ancient Egyptian history and beyond, so check in out!

On a positive note, we can appreciate the sustainability of the Egyptian textile industry. With increased documentation of the textile industry’s ignominious status as one of the globe’s major polluters, efforts to recycle, up-cycle, and repurpose leftover textiles are now of the utmost importance. Textiles never went to waste in the ancient world. From repairing a damaged tunic to turning your leftover clothes into bandages to mummify your deceased relative, ancient Egyptians made sure nothing was wasted. So as we get all anti-patriarchal, let’s try to do the same.

If you would like to get involved aiding global textile workers and fighting textile waste consider donating or getting involved:

Great article, Jordan. Thanks for sharing. On the opposite end of the spectrum, I sell hand made garments and accessories. Even just paying myself for the labor required I’m shocked by the price.