Dogs, Raging Goddesses, and the Summer Solstice in Ancient Egypt

As we celebrate the beginning of the Summer, here are a few thoughts on this most important time of the year to the ancient Egyptians.

For those of us in the Northern Hemisphere, its really starting to feel like summer! The Sun has officially moved into Cancer, the days are long and hot, children play outside, newly freed from an arduous school year and we’re all taking full advantage of the extra hours of daylight. The roar of the air conditioner, the drone of crickets on a hot night, the excitement of planning a summer trip; the dog days of summer are here at last! Wait, dog days? What does that even mean? The answer to this question lies in the stars.

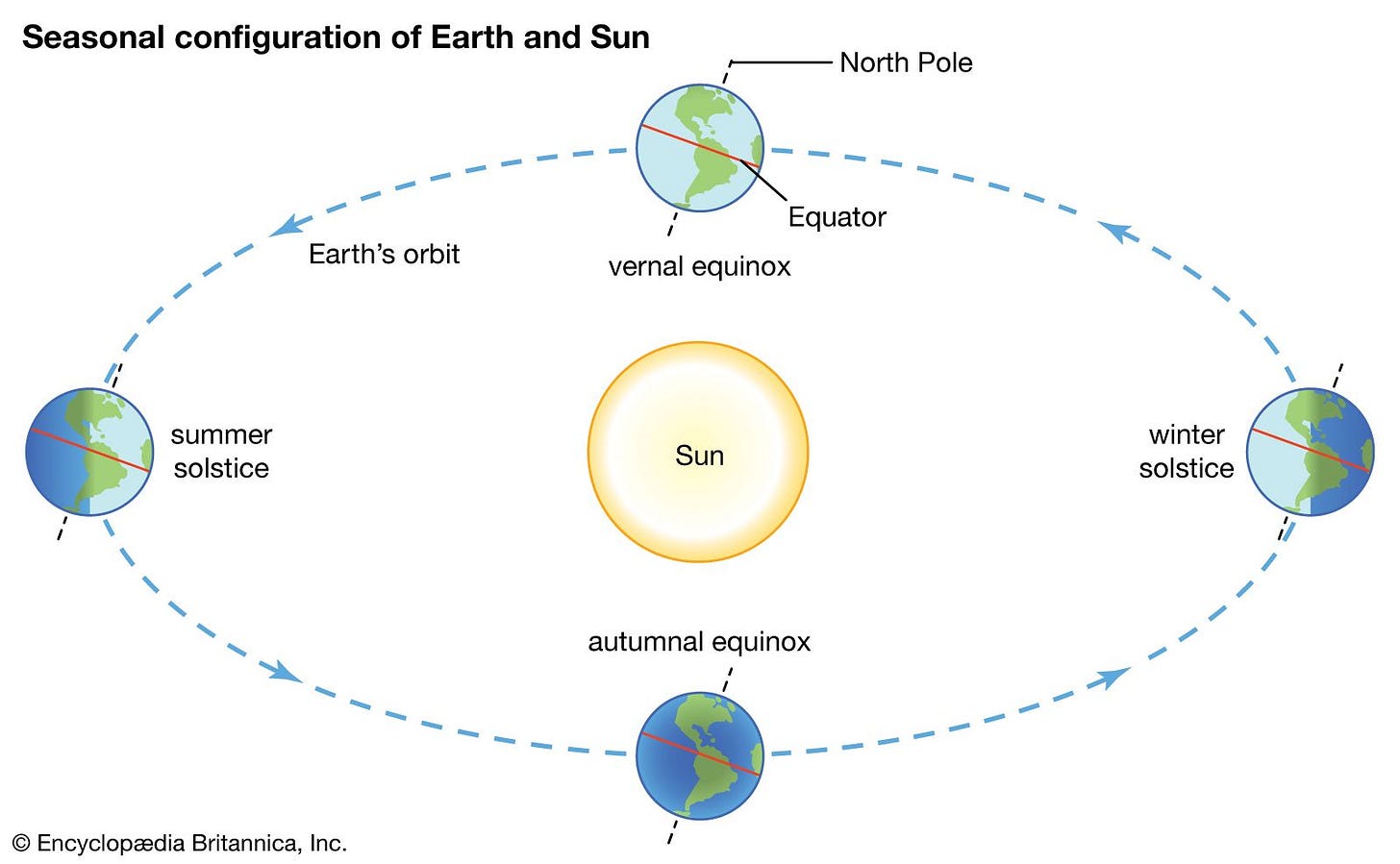

Do you know of any celestial dogs? Of course you do – Canis Major, the great dog-shaped constellation visible in the winter sky from December to March and the brightest star in the sky, Sirius (the dog star, Sopdet to the ancient Egyptians). But how does a winter constellation describe the hottest time of the year? It all has to do with the axis of Earth’s rotation and our orbit around the Sun. For those of us dwelling in the Northern Hemisphere (the ancient Egyptians included), the tilted axis of the Earth points toward the Sun in the summer.

Likewise, our view of the night sky slowly changes as Earth moves in orbit around the Sun. Thus, Canis Major rises later and later in the nighttime sky from Winter to Spring, until it coincides with the sunrise. This confluence happens around the Summer Solstice. Hence the phrase “dog days of Summer.” At dawn, the interference of the Sun’s light gradually overwhelms the light of these more distant stars, leaving only the brightest examples visible for a fleeting few minutes. These are called heliacal risings. For this reason, many ancient cultures singled out the brightest stars in the night sky and tracked their relative position at dawn or dusk as a means of situating oneself in the cyclical change of seasons.

Tracking the Stars

It is likely that this practice is very ancient, predating even the oldest sedentary agricultural societies. Time keeping facilitates both memory and foresight, hallmarks of what it means to be human and some of the most powerful facilitators of our remarkable adaptability. Think about how essential it was for our ancient relatives to discern the time of year. It allowed them to know when to stay, when to move, when to catch prey during migrations or birthing seasons, when the rains arrive, when/where to pasture animals, when to plant crops and much more. Intimately connected to the passage of seasons was their ritual commemoration (i.e. “rites of passage”). Beyond celebration, the staging of ritual was a technical business. The right time, place, materials and ritual actors were vital and often conservative elements of a ritual, tied to its very efficacy. Should the timing be wrong, the entire process could spell destruction for the community involved.

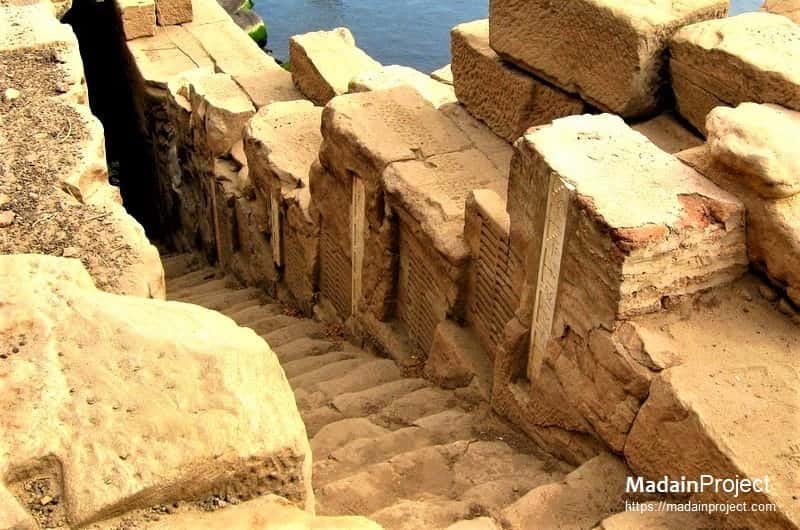

This brings us to Egypt, where, let’s say, one might be concerned with the timing of the flood of a particular river. Egypt, as the cliché goes, was the gift of the Nile. Beyond Herodotus, a slew of indigenous hymns to various riverine gods express the same sentiment. Part of the “gift” that is the Nile is its (relative) regularity. Monsoonal rains reaching the Ethiopian highlands occur around the same time each year, causing the swelling of the Blue Nile. Down and down it goes until its confluence with the White Nile at Khartoum, inaugurating the flood of the main channel. This occurred in Egypt between June or early July depending on the strength of the monsoonal rains and the location of one’s Nilometer. The process was so foundational to life on the Nile that its beginning inaugurated the New Year (Wepet-Renpet in Egyptian). The Egyptians used the Nile flood, along with several other stellar observations to reckon their calendar.

Sirius-ly Stellar

The first was the heliacal rising of Sopdet. As mentioned, one manifestation of this goddess was the star we call Sirius. Sopdet herself was a goddess venerated most notably at Elephantine, an island at the First Cataract of the Nile and a traditional “source” of the inundation to the Egyptians. Her consort was Sah, a personification of the neighboring constellation Orion, often associated with Osiris by the Egyptians. As such, Sopdet is often equated with Isis and played important roles in the death and resurrection of the king/Osiris in the Pyramid Texts. This “Osiris Cycle” held strong metaphorical and ritual associations with the Nile inundation cycle, hence her main epithet as the “bringer of the Flood.” Her name means something like “sharp/effective” and is determined with a triangular hieroglyph, perhaps a reference to the triangular group of stars that make up the head of the Greco-Roman Canis Major. By the Greco-Roman period or perhaps earlier, the Egyptians identified this constellation as a canine, although more specifically the jackal deity Anubis. Earlier representations (even as early as the First Dynasty) see the constellation as a recumbent cow with a plant-like emblem between her horns, perhaps an early rendering of the akhet hieroglyph, the word for the inundation season.

The exact date of this “Sothic-rising” is subject to some debate depending on where in Egypt the observation occurred, but it was around July 7th. This observation marked the start of the Egyptian civic calendar, commemorated by the so-called “second” New Year’s Festival on the “1st Month of the Inundation Season (Akhet), Day 1.” As the name of the season implies, this marked the “official” beginning of the Nile inundation, a time fraught with uncertainty. Although temporally reliable, the level of the Nile flood was subject to some fluctuation, and according to both ancient and medieval accounts, there was a rather narrow “Goldilocks” zone of acceptable flood heights. Too much water was equally as dangerous as too little. Both extremes could cause widespread famine and disease. It is understandable then why the “emergence” of Sopdet on the horizon was one of the most anticipated and ritually charged times of the year.

Raging Goddesses

This time was so ritually charged that the Egyptians celebrated not one but two new year’s festivals at the beginning of summer. The “First” New Years Festival was tied to a different mythological tradition centered around the Summer Solstice and a wrath of a particular goddess. Gods were fluid and overlapping entities to the Egyptians. None more so than the Sun god and his daughter(s). Many traditions saw the Sun and Moon as the “eyes” of the god Ra. The solar disk visible in the sky was often personified as the feminine “eye of Ra,” an epithet that could describe many female solar deities, most prominently Hathor and Sekhmet. They were also considered his daughters.

The tradition is variously referred to as the “Myth of the Heavenly Cow” and/or “The Destruction of Mankind,” and can be found inscribed in the tombs of several New Kingdom pharaohs. The story goes that mankind was growing rebellious against Ra. As punishment, he summoned his fiery “eye” (i.e. the hot Egyptian Sun) in the form of Hathor (cow) or Sekhmet (lion). The goddess proceeds to wreak utter destruction on mankind, starting in the north and pushing south into Nubia. At this point, Ra decides that enough is enough and sends messengers to bring back his daughter from the south and end her carnage. However, the goddess is too powerful for even the messengers of Ra to control, so through various means of trickery, including temptations of alcohol and sex, she is satiated and returned back to Egypt.

The journey of this goddess from north to south was a powerful metaphor for the changing position of the sunrise throughout the year, again due to the axis of the Earth’s rotation. The Summer Solstice in particular represents the northern limit of the rising of the sun on the eastern horizon, which inches north each day from the Winter Solstice. As such, the Egyptians equated this day with the return of the goddess from her destructive campaign in the south and the end of Ra’s punishment of mankind. The Egyptians celebrated this day as the “First New Year’s Festival,” which according to ancient documentation occurred around the “4th Month of Summer (Shemui), Day 19,” some eleven days before the rising of Sothis and the “Second New Year’s Festival.” Both traditions had strong connections with the renewal of the cosmos and the return of the blessings of the gods, whether it be the love of Ra towards mankind or the resurrection of Osiris and the return of the floodwaters so critical to life on the Nile. This was what the Egyptians considered “maat,” or the correct or natural order of the world.

So as you grill with friends, relax by the pool, or return from your own Summer campaign of utter destruction, look to the sky and give thanks to those celestial goddesses who herald in the dog days of Summer!

Jeffrey Newman is a Phd Candidate in Egyptology at the University of California, Los Angeles specializing in kingship and festivals in the pre- and Early Dynastic periods

Further Readings:

Richter, B. A. (2010) On the heels of the wandering goddess: The myth and the festival at the temples of the Wadi el-Hallel and Dendera. Interconnections between temples. 155–186.

Ezz ali, Mona (2021) Goddess Sopdet in Ancient Egyptian Religion. Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality. [Online]

Guilhou, N. (2010) Myth of the Heavenly Cow. UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology. 1 (1), .

Leitz, Christian 1991. Studien zur ägyptischen Astronomie, 2nd revised ed. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen 49. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.