Artifact Stories: Khufu’s itty, bitty ivory statuette

What do we know about one of the only surviving, mostly complete 3D images of the builder of the Great Pyramid?

One of the best pieces of advice I gave museum visitors as a Getty museum educator was to slow down as they explored the galleries and look for the smallest artifacts on display. You’re almost guaranteed to have a unique museum experience, given that most visitors will sweep their eyes over the gallery space and land on the most visually attractive displays and miss the “small things forgotten” and, therefore, limit the stories they read about the past. When you do some “close-looking,” you discover details about artifacts that most people will miss.

In the spirit of this idea, we are producing a new series of episodes for Afterlives of Ancient Egypt called “Artifact Stories,” in which we choose one thing—be it art, artifact, architecture, etc.—and dive into the details in order to see what insights and perspectives we can draw from it. For each of these episodes we will be publishing a companion post here on Ancient/Now.

In our first spotlight discussion (Afterlives of Ancient Egypt, Season 3, Episode 17) we featured an object whose diminutive size belies the significance of the story it tells about the reign of the 4th Dynasty king, Khufu (ca. 2589-2566 BCE), who most people know as the builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Listen to the podcast episode:

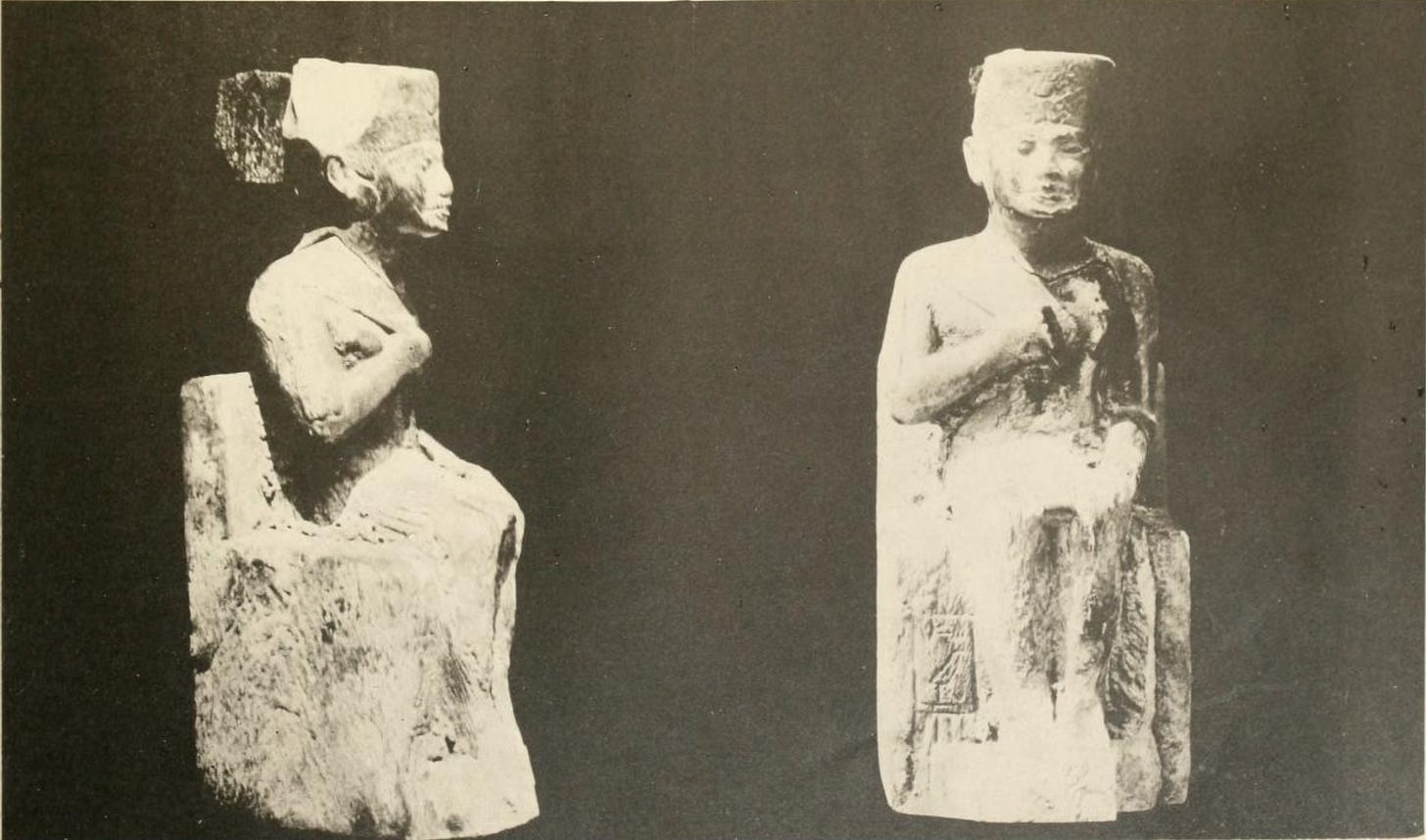

This ivory statuette of a seated Khufu (Egyptian Museum, Cairo; JE 36143) was excavated in the temple complex of Osiris-Khentyimentiu at Abydos by archaeologist William Flinders Petrie in 1903. It is only 7.5 cm high and about 2.5 cm wide, and no doubt owes its small size in part to the expensive, hard-to-obtain ivory from which it’s made (elephant hunting and killing, most likely). Khufu is seated on a throne, beardless, wearing the red crown, and holding a flail in his right hand, which is resting on his chest. His left hand rests with an open palm on his knee. He is wearing a short, pleated kilt and is naked from the waist up. The throne on which the king sits is undecorated, except for Khufu’s name, which is written on the front of the throne. The feet and footrest are missing, broken away from the figure.

Based on art historical analysis, most Egyptologists date this statue to the reign of Khufu, but there is a lot of disagreement about the date. Note that Egyptologist Zahi Hawass (1985) has argued for a 26th Dynasty date. He maintains that there was no activity at the temple complex of Osiris-Khentyimentiu in Abydos during the 4th Dynasty, despite evidence that there was building activity there by Khufu and that the temple may have been dedicated to a later cult of Khufu (see Bussmann, 2007).

Unfortunately, the statuette’s head was knocked off during excavation. When Petrie saw the small, headless ivory figure and read the name inscriptions on the base, he recognized its significance and had the debris from the site of its discovery carefully searched and was able to recover the head after “three weeks [!!!] of incessant sifting.” (Petrie et al., 30) At the time of its discovery Petrie described it as “the first figure of that monarch that has come to light,” which explains why he was so willing to dedicate three precious weeks of his excavation season to finding the statuette’s missing head (Petrie et al., 30). Petrie’s description of the statuette reveals his excitement about the discovery, and how taken he was with the idea of Khufu as a powerful king:

The idea which it conveys to us of the personality of Khufu agrees with his historical position. We see the energy, the commanding air, the indomitable will, and the firm ability of the man who stamped for ever the character of the Egyptian monarchy and outdid all time in the scale of his works. No other Egyptian king that we know resembled this head; and it stands apart in portraiture, though perhaps it may be compared with the energetic face of Justinian, the great builder and organizer.

Since 1903, alabaster fragments of seated statues of Khufu were found by George Reisner at Giza and Rainer Stadelmann. Stadelmann (1998) has suggested that fifty or so statues of the king must have existed at his mortuary temple. Over twenty statues of Khufu were taken over later by his son Djedefre (we know Djedefre reused the statues because Khufu’s names are still inscribed on them). Additionally, the Palermo Stone describes two colossal statues of Khufu made of gold and copper, but they did not survive—likely because they were made of valuable and easily reusable materials. Still, the ivory statuette of Khufu is notable as the only surviving, relatively intact three-dimensional representation of the king.

In The Good Kings Kara discusses the impression royal art and architecture were intended to convey to various audiences (e.g. other elites, the average everyday Egyptian). She discusses this well-known statuette of Khufu, an image of the king made of ivory--a precious material that can only be obtained (one assumes, with great skill and expense) from an elephant, or maybe a hippopotamus. By using ivory as the medium for this figurine, Kara argues, Khufu’s statuette evokes “the human power required to bring down such a creature.” If the king had the ivory to make this statuette, then he had the power to fell an elephant, making this object a trophy display speaking directly to that power.

And then there is its size to consider. Yes, it’s made of ivory and one cannot expect a figure made of that material to be monumental in scale, but, we might wonder: couldn’t it have been a little bigger? It is so small! To some experts the small size suggests a personal, private use rather than public display. (If you’ve listened to the podcast episode, you know that Kara is not convinced by this argument and leans toward the idea that it may have had a cultic function. Ivory was mega-prestigious, after all.) In The Good Kings Kara suggests that Khufu intentionally limited the production of his personal image. From that perspective, the fact that this statuette is one of the only three-dimensional images of Khufu to have survived relatively intact is not that surprising.

With its ambiguous archaeological context, drawing any firm conclusions about the ancient life of this ivory statuette of Khufu is difficult. Was possession of this little statue kind of like owning a modern military challenge coin, indicative of a connection, status, and proximity to the king, or did it have a much greater cultic role in the temple in which it was found? How can we know what messages were meant to be conveyed by such an ancient artifact? It’s always preferable for Egyptologists to have primary documents written by the (elite!) ancient Egyptians themselves to back up their analysis, but in most cases, they have to make strong circumstantial arguments based on incomplete evidence combined with their insights and observations from years of study and research immersed in the ancient evidence.

Bibliography

Bussmann, Richard. 2007. Die Provinztempel Ägyptens von der 0. bis zur 11. Dynastie. Probleme der Ägyptologie, Vol. 30. Leiden: Brill, 90, 147, 467.

Hawass, Zahi. 1985. The Khufu Statuette: Is it an Old Kingdom Sculpture? In: Posener-Kriéger, Paule (ed.), Mélanges Gamal Eddin Mokhtar, Bibliothèque d'étude, 97 (1). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale du Caire.

Petrie, W. M. Flinders, E. R. Ayrton, C. T. Currelly, and A. E. Weigall. 1902-1904. Abydos, Vol. 2. Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund 22; 24; [25] special extra publication. London: Egypt Exploration Fund; Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co, 30, Pl. XIII (full), Pl. XIV (detail).

Stadelmann, Rainer. 1998. Formale Kriterien zur Datierung der königlichen Plastik der 4. Dynastie. In: Grimal, Nicolas, Les critères de datation stylistiques à l'ancien empire. Le Caire: Institut français d'archéologie orientale, 353-387.

This was a fun episode! Kara’s ability to find the sexual element in just about anything is amazing. I stand in respectful awe 😍