In this episode Kara and Jordan answer listener questions from April. To submit a question for the monthly Q&A podcast, become a paid subscriber on Substack or join our Patreon!

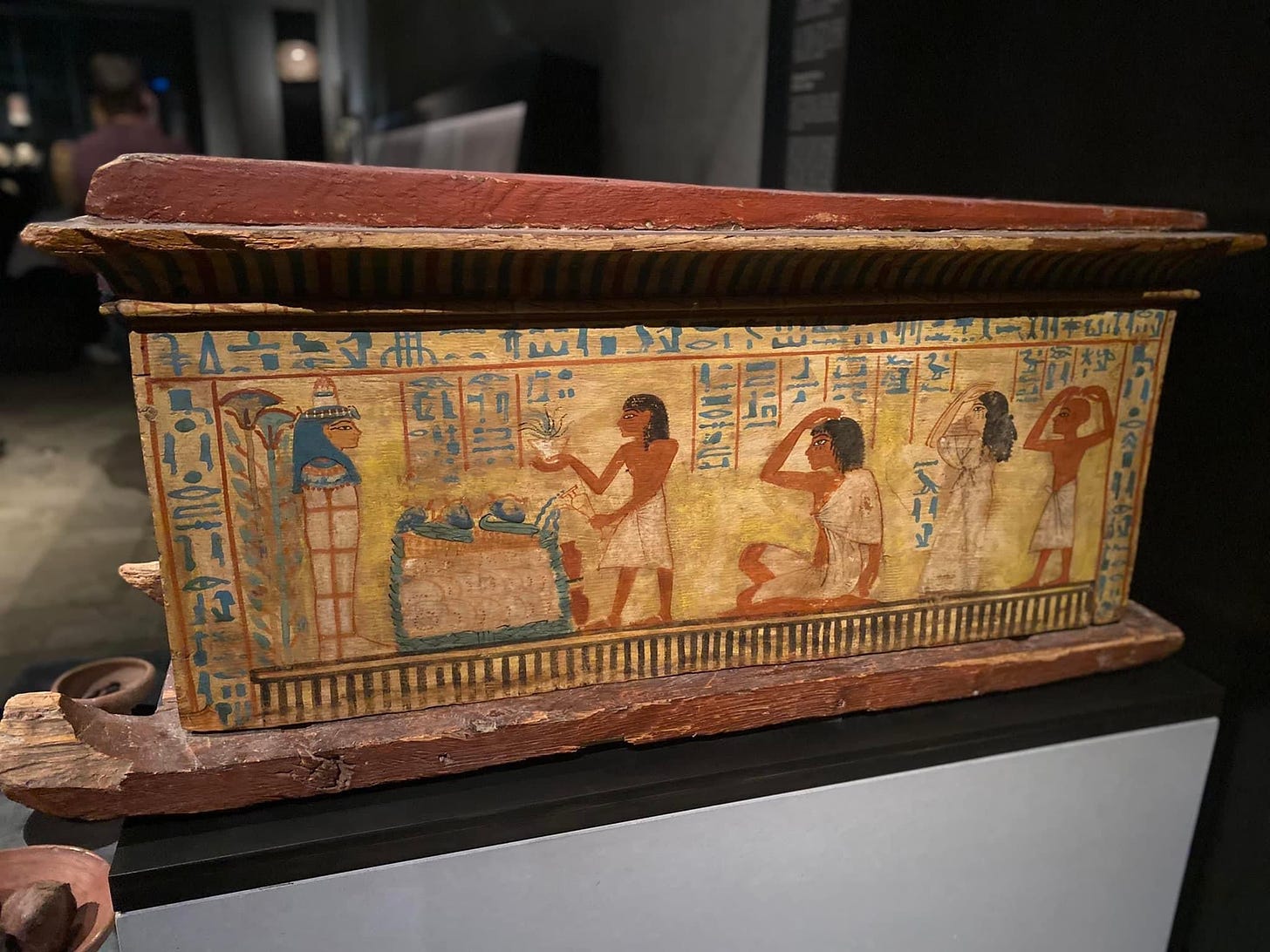

A few photos from Kara’s Egypt trip

Show Notes:

Female Genitalia Lexicography

Bednarski, Andrew 2000. Hysteria revisited. Women's public health in ancient Egypt. In McDonald, Angela and Christina Riggs (eds), Current research in Egyptology 2000, 11-17. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Ghalioungui, P. 1977. The persistence and spread of some obstetric concepts held in ancient Egypt. Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Égypte 62, 141-154.

Westendorf, Wolfhart 1999. Handbuch der altägyptischen Medizin, 2 vols. Handbuch der Orientalistik, erste Abteilung 36 (1-2). Leiden: Brill.

Burial of Children

Barba, Pablo 2021. Power, personhood and changing emotional engagement with children's burial during the Egyptian Predynastic. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 31 (2), 211-228. DOI: 10.1017/S0959774320000402.

Kaiser, Jessica 2023. When death comes, he steals the infant: child burials at the Wall of the Crow cemetery, Giza. In Kiser-Go, Deanna and Carol A. Redmount (eds), Weseretkau "mighty of kas": papers in memory of Cathleen A. Keller, 347-369. Columbus, GA: Lockwood Press. DOI: 10.5913/2023853.22. Export >>

Marshall, Amandine 2022. Childhood in ancient Egypt. Translated by Colin Clement. Cairo; New York: American University in Cairo Press.

Saleem, Sahar N., Sabah Abd el-Razek Seddik, and Mahmoud el Halwagy 2020. A child mummy in a pot: computed tomography study and insights on child burials in ancient Egypt. In Kamrin, Janice, Miroslav Bárta, Salima Ikram, Mark Lehner, and Mohamed Megahed (eds), Guardian of ancient Egypt: studies in honor of Zahi Hawass 3, 1393-1403. Prague: Charles University, Faculty of Arts.

Skin Color and Gender

Shelley Halley, Prof. Emerita of Classics and Africana Studies, Hamilton College

Tutankhamun out of the lotus blossom with ‘naturalistic’ skin

Roth, Ann Macy 2000. Father earth, mother sky: ancient Egyptian beliefs about conception and fertility. In Rautman, Alison E. (ed.), Reading the body: representations and remains in the archaeological record, 187-201. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Kara’s ARCE Talk- “Elites Relying on Cultural Memory for Regime Building”

Abstract: Theban elites of the late 20th and 21st Dynasties relied on veneration of 17th and 18th Dynasty kings to support their regimes ideologically. The cults of Ahmose-Nefertari and Amenhotep I were vibrant in the west Theban region, and their oracles were essential to solving many disputes. Herihor connected his militarily-achieved kingship to his position in the Karnak priesthood using the ancestor kings as touchstones. Twenty-first Dynasty Theban elites named their children after 18th Dynasty monarchs; Theban High Priest and king Panedjem named a daughter Maatkare, ostensibly after Hatshepsut of the 18th Dynasty, and a son Menkheperre after Thutmose III. Examination of the 20th and 21st Dynasty interventions of the royal mummies from Dra Abu el Naga and the Valley of the Kings indicates these royal corpses were used as sacred effigies of a sort, rewrapped and placed into regilded containers even after they had been stripped of their treasures and golden embellishments. This paper will examine how immigrants and mercenaries were able to move into Theban elite circles by marshaling ancestral connections to power. Men like Herihor and Panedjem, one of them at least of Meshwesh origins, worked within an Upper Egyptian cultural system that put its temple communities of practice before its military and veiled its politics with pious rituals and oracular pronouncements. Such elites had to negotiate their identities and power grabs through the cultural memory of the region’s royal ancestors.

Episode 83- Thutmose III and the Veneration of the Royal Ancestors

Cooney, Kathlyn M. 2022. The New Kingdom of Egypt under the Ramesside dynasty. In Radner, Karen, Nadine Moeller, and D. T. Potts (eds), The Oxford history of the ancient Near East, volume III: from the Hyksos to the late second millennium BC, 251-366. New York: Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780190687601.003.0027.

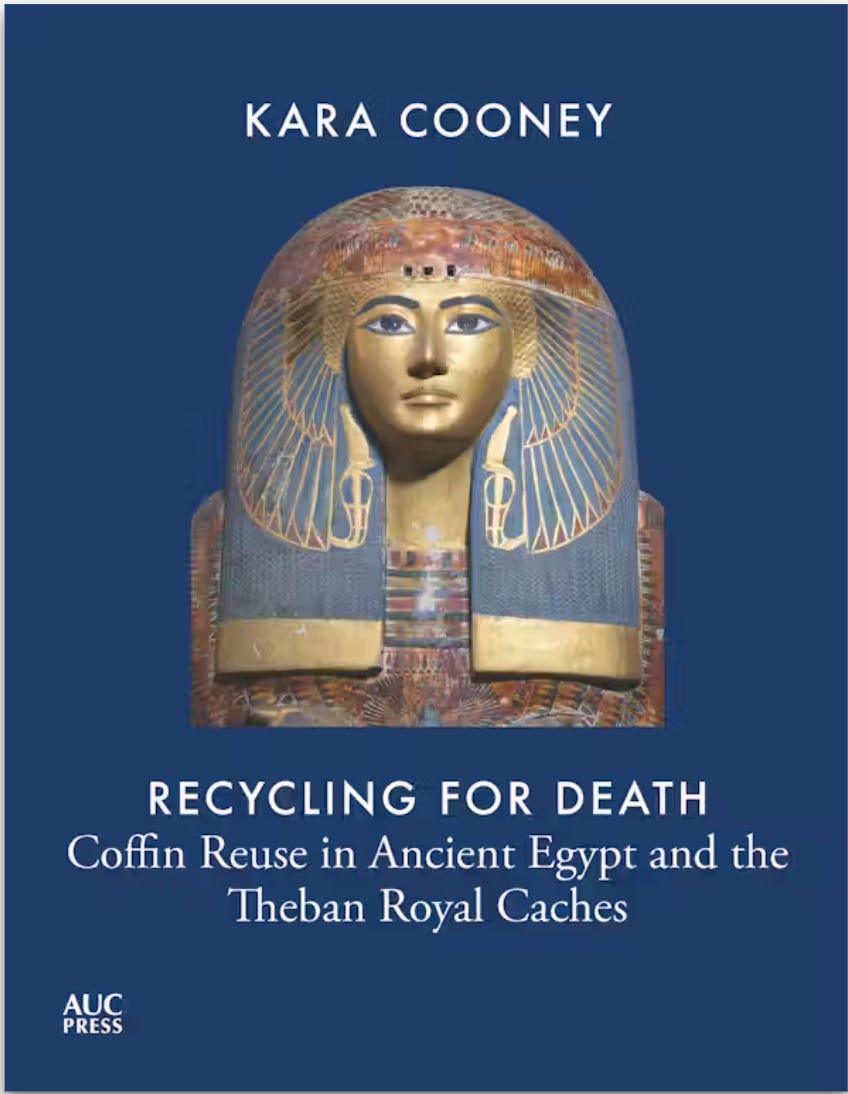

Cooney, Kara. 2024. Recycling for Death AUC Press.

Share this post