Ancient/Now - May 22nd

Netflix's "Queen Cleopatra" docu-drama garners awful reviews, declassified documents reveal internal British conflict over Elgin Marbles, the destruction of Djedefre’s pyramid causeway and more

Bad reviews for Netflix’s Queen Cleopatra

Netflix’s docu-drama Queen Cleopatra hit streaming this month, and audiences are underwhelmed. While actress Adele James’ strong performance as Cleopatra carries the production, the historical accuracy of the story it tells is fuzzy at best and any attempts at sticking to the facts are frequently overshadowed by the opinions and personal interpretations expressed by the featured experts. Meanwhile the controversy over casting a Black actress to play Cleopatra continued to swirl, fueled by a spectrum of mixed reviews from outlets like the BBC, The New York Times, The Guardian, Slate, and a hastily released competing documentary from Curtis Ryan Woodside and Zahi Hawass that has the explicit intent of arguing that Cleopatra was not Black but “had” to be of “pure Macedonian Greek blood.” Tina Gharavi, the director of Queen Cleopatra, spoke out and acknowledged her specific intention to use the production as an opportunity to present a “re-imagined Cleopatra” in an editorial published by Variety:

I am proud to stand with “Queen Cleopatra” — a re-imagined Cleopatra — and with the team that made this. We re-imagined a world over 2,000 years ago where once there was an exceptional woman who ruled. I would like to draw a direct line from her to the women in Egypt who rose up in the Arab uprisings, and to my Persian sisters who are today rebelling against a brutal regime. Never before has it been more important to have women leaders: white or Black.

Bottom-line? If you choose to check out one or both of these newly released productions on the life of Cleopatra, keep in mind that neither of them present an unbiased history, nor should either one be considered a final, last-word, authoritative source on the life of Cleopatra VII. Given the nature of the surviving historical and archaeological evidence and the pervasive ancient and modern propaganda surrounding this iconic queen, a full and complete history of her life is just not something that we will ever have.

If you want a more academic discussion of Queen Cleopatra and the historical figure of Cleopatra VII, you should check out Dr. Rebecca Futo Kennedy’s (Associate Professor, Denison University) short interview with NPR and her appearance on The Travis Smiley Podcast:

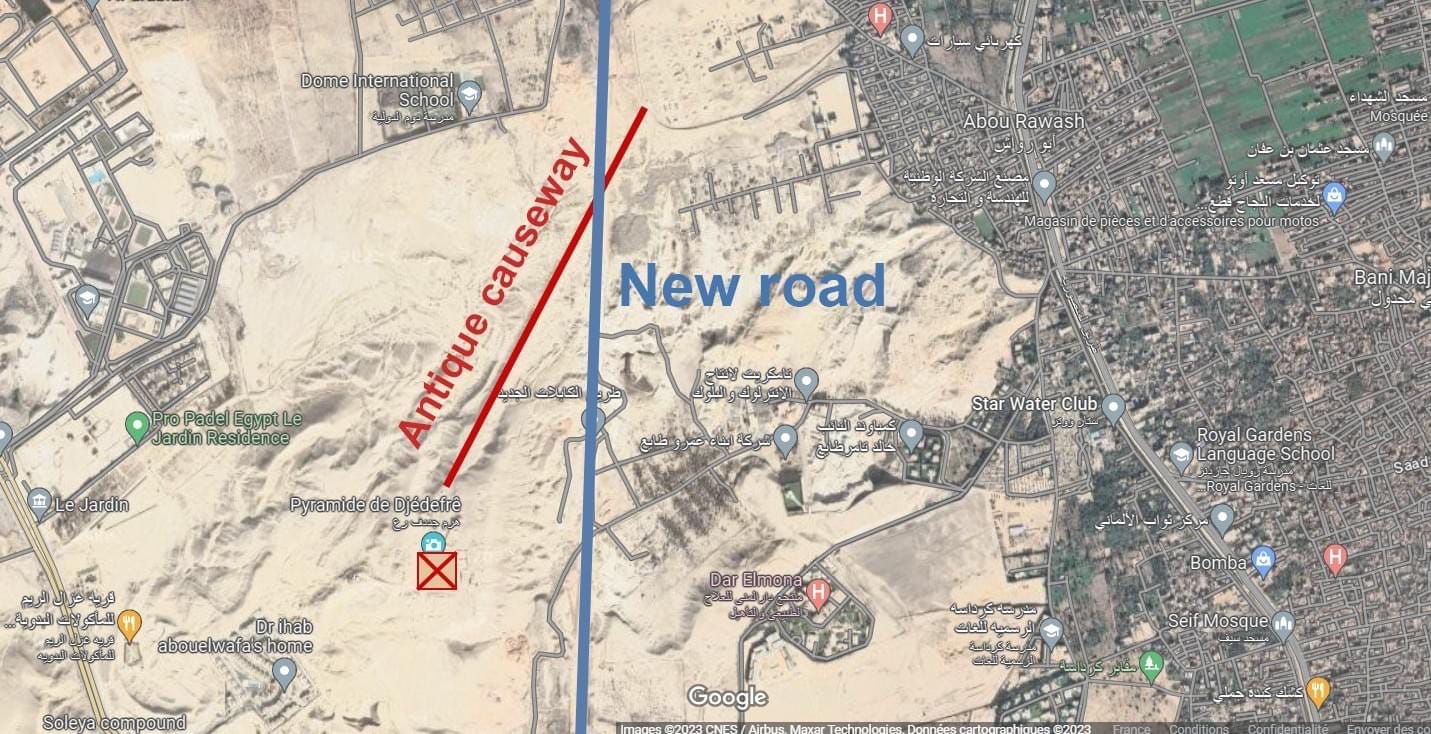

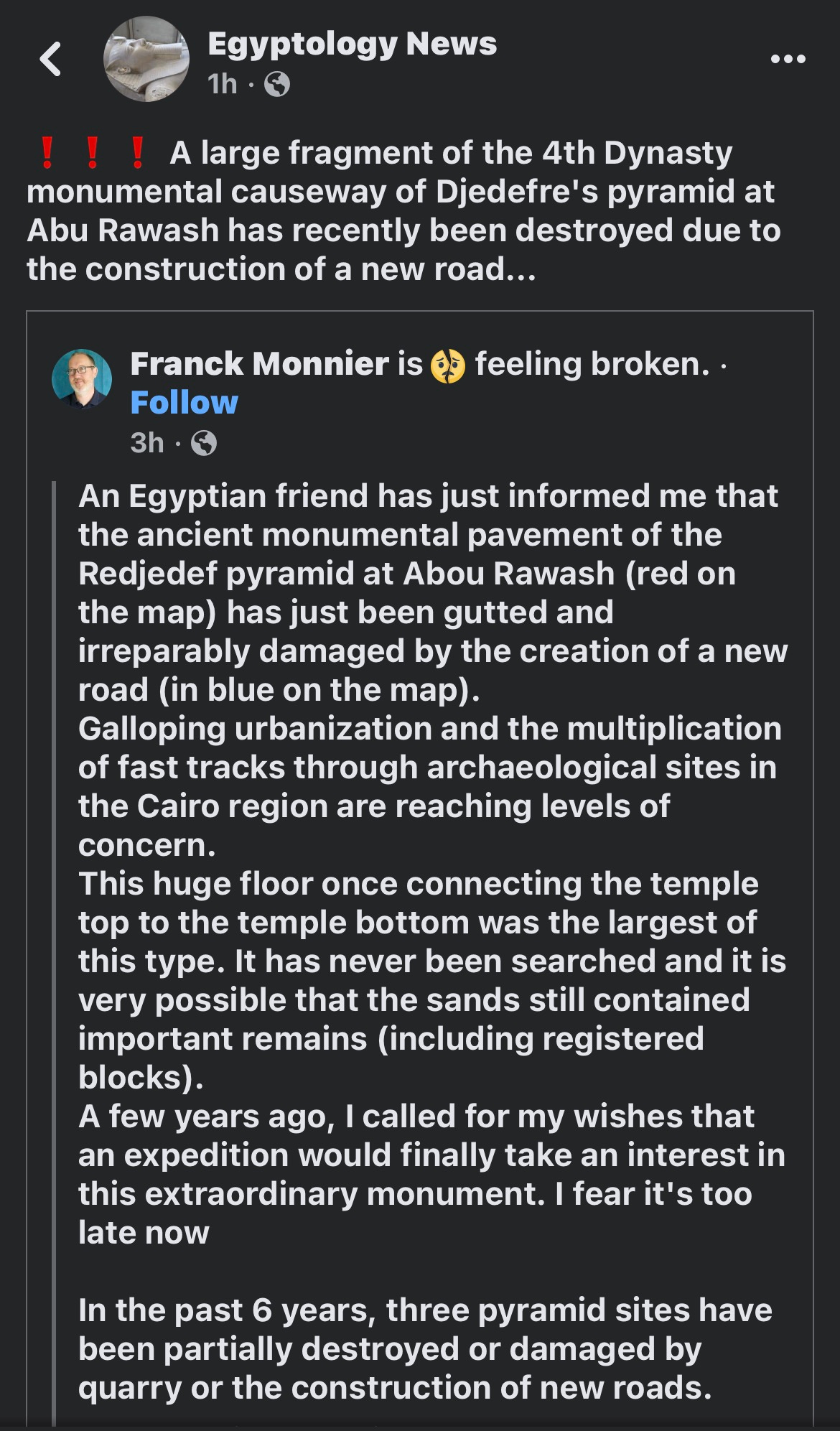

Causeway of Djedefre’s pyramid at Abu Rawash destroyed by construction

“Egyptology News” recently reported on Facebook that a significant portion of the causeway of king Djedefre’s pyramid at Abu Rawash has been destroyed to make way for the construction of a new road. As the post below from Franck Monnier (researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and co-founder of the Journal of Ancient Egyptian Architecture) laments, urban encroachment on ancient Egyptian archaeological sites has long been an issue of concern, but the current rates of destruction by construction and development are reaching alarming levels. Over the weekend @BlueCairo tweeted about the destruction of the burial place of Abdullah Bek Zohdi, known as the Calligrapher of the Prophet Mohammed’s mosque in Medina, in Cairo’s Islamic-era necropolis known as the “City of the Dead.” Unfortunately the level of protection for ancient and historical sites in Egypt is subject to the priorities of political and institutional leaders, and those priorities don’t always coincide with best archaeological practices.

And we hope we are not throwing stones from glass houses; the United States has its own development projects that bulldoze over ancient sites, such as this one about War-Mart’s history of destroying sacred Native American sites. For a broader picture of the destruction of cultural heritage in America, check out this list of destroyed heritage sites in the United States.

Declassified documents tell of conflict between British Museum and UK Government

And now for more post-colonial competitive drama over who owns the past! Earlier this month ARTnews reported on the release of newly declassified documents, some of which date to the 1980’s, related to the Parthenon Marbles. Taken from the Parthenon in Athens by British aristocrat Lord Elgin in the early 19th century and brought to England, these ancient Greek sculptures now housed in the British Museum are a continuing source of controversy. The Greek government has long ago asked for the return of the Marbles, but the BM conveniently hides behind a 1963 law (the British Museum Act) that denies the museum the ability to deaccession anything from its collection and will not consider their repatriation to Greece. (So the British argument essentially boils down to something like, “We can’t return the Elgin Marbles to Greece because we made a law saying we can’t!”)

The declassified documents—released by the United Kingdom’s National Archives, include communications between the British Museum and the UK government, as well as other organizations—tell us that British opinion on the Parthenon Frieze has been more divided than previously known. The documents provide interesting insight into a spirited, internal, British debate surrounding the Marbles, the government’s decisions regarding the issues surrounding their ownership and future, and the legal and diplomatic considerations surrounding the BM’s refusal to return them. The declassified materials reveal the Foreign Office’s dismissive attitude toward the BM’s desire to maintain their ownership of the Marbles and, most interestingly, that British officials were unimpressed with the museum’s arguments in favor of their continued possession of the Marbles:

The report also recorded sentiments that Brian Cook, the British Museum’s curator of classical antiquities, was just as ineffective at debating Mercouri [Greek culture minister] as Wilson [BM director] had been. In another meeting during her visit, Cook made “a disappointing and pedantic defence, aimed at proving that Elgin was not guilty of vandalism and that the Parthenon was a symbol of Athenian imperialism, not Greek freedom and nationhood.”

It is as yet unclear what the full implications of the declassified documents are and what they might mean for the debate on the Marbles and the international repatriation of cultural objects, particularly since it seems that some UK government officials were in favor of returning the Parthenon Frieze, knowing that the controversy would haunt the nation in the decades to come. In 1983 a proposal existed to amend the 1963 British Museum Act and allow the BM to return the Marbles, but it was ultimately rejected. ARTnews writes,

Former Labour arts minister Hugh Jenkins proposed amending this act to allow deaccessioning in May 1983, ahead of Mercouri’s visit. The amendment was opposed by the conservative government at the time and failed to pass—a move which arts minister Paul Channon noted in the Foreign Office file. The marbles’ return would “start a process of piecemeal break-up of the British Museum collections,” he said.

The British Museum has staunchly resisted repatriation when it comes to iconic antiquities like the Rosetta Stone and the Elgin Marbles, and their already-weak arguments for holding on to them continue to crumble. How much longer will they be able to resist?

New episodes of Afterlives of Ancient Egypt

Do NOT miss the latest Afterlives Bookclub episode: “Don’t bring a Mace to a Gun Fight—Barbara Michaels’ ‘Search the Shadows.’” If you like Barbara Mertz’s novels with an Egyptology angle, you will love this one. But unless you’re okay with spoilers, you should read the book first!

What else were we reading this week?

Producer-director Neil Laird’s review of Kara’s book, The Good Kings: Absolute Power in Ancient Egypt and the Modern World, caught our eye. He writes that The Good Kings is

…a 400-page history book bursting with characters, controversies, and enough food for thought to stock the afterlife. As Cooney persuasively remarks in her opening chapter: “The truth is, we think modern societies, in which leaders are voted into power, are different from ancient kingships. But all we do today is hide our desires for a king from ourselves.”

Laird concludes that with this book Kara “challenges readers to rethink their perceptions of well-known rulers in history”—it seems he was a reader who appreciated the challenge!

Kara was also in The New York Times last week, which published a story (featuring several great quotes from Kara) on the severed hands discovered at Avaris that were taken as trophies of war by the ancient Egyptians. We discussed this discovery in the April 17th edition of Ancient/Now.

And then were a whole lot of other ancient-related things in the news this past week, including new finds and political fights over old finds. Check out the links below!

Four smuggled Ancient Egyptian artefacts arrive home from Italy

Byzantine and Late Period relics uncovered in Meir necropolis in Assiut

Artifacts uncovered in Ismailia’s Tell al-Maskhuta

After Decades of Looting, Mosul Museum Plans to Reopen

The Dangerous Allure of the Royal Aesthetic

Diver unexpectedly discovers Roman-era shipwreck carrying beautiful marble columns off Israel's coast

2,300-year-old scissors and 'folded' sword discovered in a Celtic cremation tomb in Germany

2,000-Year-Old Iron Age and Ancient Roman Pottery Unearthed by Metal Detectorist in Wales

Forgotten Sections of Roman Wall That Once Surrounded London Found Near the Thames

'Lost' bacteria found on Neanderthal teeth could be used to develop new antibiotics

One more thing…

Dr. Robert Cargill, Associate Professor of Biblical Studies at the University of Iowa, recently made an observation about the movie poster for Gal Gadot’s upcoming Cleopatra film that the Greek readers among us will appreciate: