Ancient/Now - May 16th

A look inside ancient Egyptian animal coffins, mummified remains in a London auction house, museum provenance research teams and more

A look inside ancient Egyptian animal coffins

In the Late Period (ca. 664-332 BCE), the ancient Egyptians made all these hollow containers in the shape of animals. We call them coffins, but it’s a fair thing to wonder what was actually put inside these boxes. A new article in Scientific Reports shares the results of a neutron tomography study of six such animal mummy coffins from the British Museum’s collection. The ancient Egyptians closely associated animals with divinities and in some contexts considered them to be manifestations of a god or goddess. During the Late Period animal cults surrounding deities were incredibly popular, and animals were raised and sacrificed for expressly religious purposes, including the creation of religiously charged objects like animal mummies—a kind of votive sent to the beyond to communicate with the gods on your behalf. (For instance, there are massive ibis (and some baboon) mummy catacombs at Tuna el-Gebel in Egypt. Ibises and baboons were animals associated with the god Thoth.) These copper alloy boxes are also sometimes referred to as “votive boxes” because animal mummies were often given as offerings at temples or other religious spaces by worshipers. By the Late Period, most temples had lost their state funding from the king and had to “privatize” and create their own income, a condition familiar to many a museum and institution of higher learning.

Now, how can researchers tell what was inside the boxes? Neutron tomography provides researchers with better imaging than X-ray computed tomography, which can’t scan through dense metal boxes. By examining the better quality neutron tomography images, researchers learned about the way the metal boxes were constructed and determined that the boxes contained actual animal remains and textile wrappings. As the article concludes,

This work provides further evidence for the use of copper alloy votive boxes in ancient Egypt, showing that animal remains were wrapped in linen and placed inside the boxes before they were sealed, and that the cast animal figures upon the boxes were potentially intended to correspond to the remains within.

This conclusion seems logical and obvious, but it is not one to be taken for granted. During the Late Period, animal mummies created a thriving business, so much so that those selling religiously charged objects like animal mummies often cut corners. We have evidence that some animal mummies contained only partial skeletons, or just a few bones, or—in come cases—no animal remains at all. Given that there was lots of money to be made by a given temple and because biological processes created natural limits on how quickly animals could be conceived, birthed, raised, and sacrificed, it’s not surprising that enterprising animal cults yielded to the impulse to increase their profits.

You can see some of the neutron tomography imaging from this study here, including this video:

How did an ancient Egyptian mummified head and hand end up in an auction Hall in London?

An ancient Egyptian mummified head and hand recently turned up at an auction house in London, and given the obvious sensitivity surrounding the trade of human remains, the Egyptian government is trying to figure out how the body parts left the country and if it was done illegally. How did these remains end up at the auction house? The article states,

According to the Swan Fine Arts, the mummified head left Egypt toward London during World War I with a British soldier who kept it in his home under a glass dome. The head, which radiocarbon dating suggests is 2,800-years-old, remained in the soldier's family for a century, however as some visitors were annoyed by the look of the head, it ended up being stored in a cupboard.

What a macabre souvenir. No surprise that the family of the British soldier now wants to part with the remains. However, should they actually be trying to profit off of them? As one official of the Egyptian government pointed out, it’s unethical to put human remains up for auction. That any auction house would agree to sell human remains—especially those with an ambiguous provenance—with today’s growing awareness of of how human remains have been treated by colonial regimes and within all types of cultural institutions seems oblivious and tone deaf. Let’s hope that decency prevails and these remains are returned to Egypt where they can be respectfully received instead of being treated as a gory curiosity auctioned for a quick profit.

The Met plans to hire a provenance research team to review the museum’s collection

In recent years The Met has faced law enforcement investigations resulting in the seizure of looted artifacts and an ever-growing number of calls for repatriation of works of art from multiple countries. Some, like Cambodia, question the museum’s right to certain cultural material. The museum now says it plans to hire a provenance research team to review its collection for looted art or objects with “problematic” histories. The piece reads:

“As a pre-eminent voice in the global art community, it is incumbent upon the Met to engage more intensively and proactively in examining certain areas of our collection,” Max Hollein, the museum’s director, said in his letter. He added that “the emergence of new and additional information, along with the changing climate on cultural property, demands that we dedicate additional resources to this work.”

The NYT article goes on to point out that other museums, like the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, also have provenance research teams, but The Met’s plan for a four-person team is credited as being particularly robust. But, is it the museum’s place to police themselves when such agendas are diametrically opposed to collection growth? Any steps to seek out antiquities that entered a museum’s collection illegally are to be commended, but these kinds of internal research teams might also seem a bit like the fox guarding the hen house. Outside investigations by law enforcement will continue to play a key role in holding museums to account for their past collecting practices.

Hollein continues,

“It’s not that we are taking objects and closing them away just because we want to own them,” he said. “We collect objects because we want to share them, we want to contextualize them, we want people to understand more about them. The Met is a very good place for works of art from across the world. It’s a very good place to connect these objects with other communities and cultures.”

This sentiment may very well be true, but the cultural zeitgeist is changing, and other communities and cultures are increasingly asserting their right to share and contextualize their own works of art—with the added argument that they are better equipped to do it.

And while we’re on the subject of repatriation, let’s leave the discussion with this thoughtful response from Patricia Marroquin Norby, the Met Museum’s curator of Native American Art, who argues that more connection with the communities of origin is needed when discussing repatriation. Such relationships are vital if museums are to begin to separate their current agendas from their colonial pasts:

For me, there is much to still love about museums but I also embrace the need for critical change. Although one person, or even a few, cannot correct all of the mistakes and hurtful actions of the past, by working collaboratively and respectfully with source communities we can, together, do everything in our power to ensure we honor our responsibilities to all communities of origin, both at home and abroad.

Research confirms high status and political power of women in nomadic Xiongnu society

Have women ever ruled the world anywhere? We keep looking… The nomadic Xiongnu people (ca. 200 BCE-100 CE) of the Mongolian steppe were known as a horseback-mounted warrior society with powerful women, but given the nomadic nature of their society, they left little in the way of archaeological evidence to support this idea aside from large stone mortuary complexes. The Xiongnu had no formal writing system and left no texts of their own, putting their culture at a disadvantage with the people who write the history books. Indeed, most accounts of the Xiongnu come from the Han Dynasty of Imperial China, which unquestionably saw the Xiongnu as rivals—they erected the Great Wall of China in part as a defense against the Xiongnu and kept records of their battles with them.

Can archaeology help? In an increasingly familiar trend, archaeologists recognizing the limits of what they could learn about the Xiongnu from excavating burials (one of which contained a faience bead depicting the ancient Egyptian god Bes!) and the written records of their enemies turned to DNA analysis of the human remains interred in the Xiongnu mortuary complexes. The Harvard Gazette writes,

In the end, the scientists harvested genome-wide data for 19 individuals, with 17 yielding sufficient human DNA for analysis. “We found that the aristocratic elite tombs were occupied by women,” said Warinner [Associate Professor of Anthropology at Harvard and biomolecular archaeologist], who went on to list some of the symbolic goods buried with them — a gilded iron belt buckle, horse tack, a wagon, an ornamental sun and moon. “I think what we’re seeing is that as armies of Xiongnu warriors were going out and expanding the empire, elite women were governing the borders,” she said.

As a group, these aristocratic women exhibited the lowest genetic diversity, Warinner added, suggesting that power was concentrated within particular lineages. As for the servants buried around them, they turned out to be a highly diverse group of males, incorporating populations from the empire’s farthest reaches and beyond.

Such biomolecular analysis of ancient human remains is leading to cultural insights and a deeper, more nuanced understanding of an ancient society that would be impossible with only traditional archaeological excavation and limited historical records. And women can rule their world…when their menfolk are off raiding.

Help protect cultural heritage in Sudan

With the crisis in Sudan, the American Sudanese Archeological Research Center has put out a call for donations to fund archaeological site inspectors and site guards so that they can continue to report to their sites and safeguard cultural heritage in Sudan. If you would like to donate, go to AmSARC’s website.

What else were we reading this week?

The Florida Principal Fired for Allowing a Lesson on Michelangelo’s ‘David’ Went to Italy to See the Sculpture Herself

The Egyptian mummy Shep-en-Isis and the thorny question of repatriation

Anemia found to be common in ancient mummified Egyptian children

A brief compendium of Egyptomania

‘Lost’ Microbial Genes Found in Dental Plaque of Ancient Humans

Historian claims to have located mystery 'Mona Lisa' bridge

Ancient DNA from a 25,000-year-old pendant reveals intriguing details about its wearer

Stunning Roman Mosaic Found Beneath UK Shopping Mall

Is a Michelangelo Self-Portrait Hidden In His Famous Fresco?

Decapitated and dismembered bodies found at Maya Pyramid

Medical prescription bottle found in South Africa

One more thing…

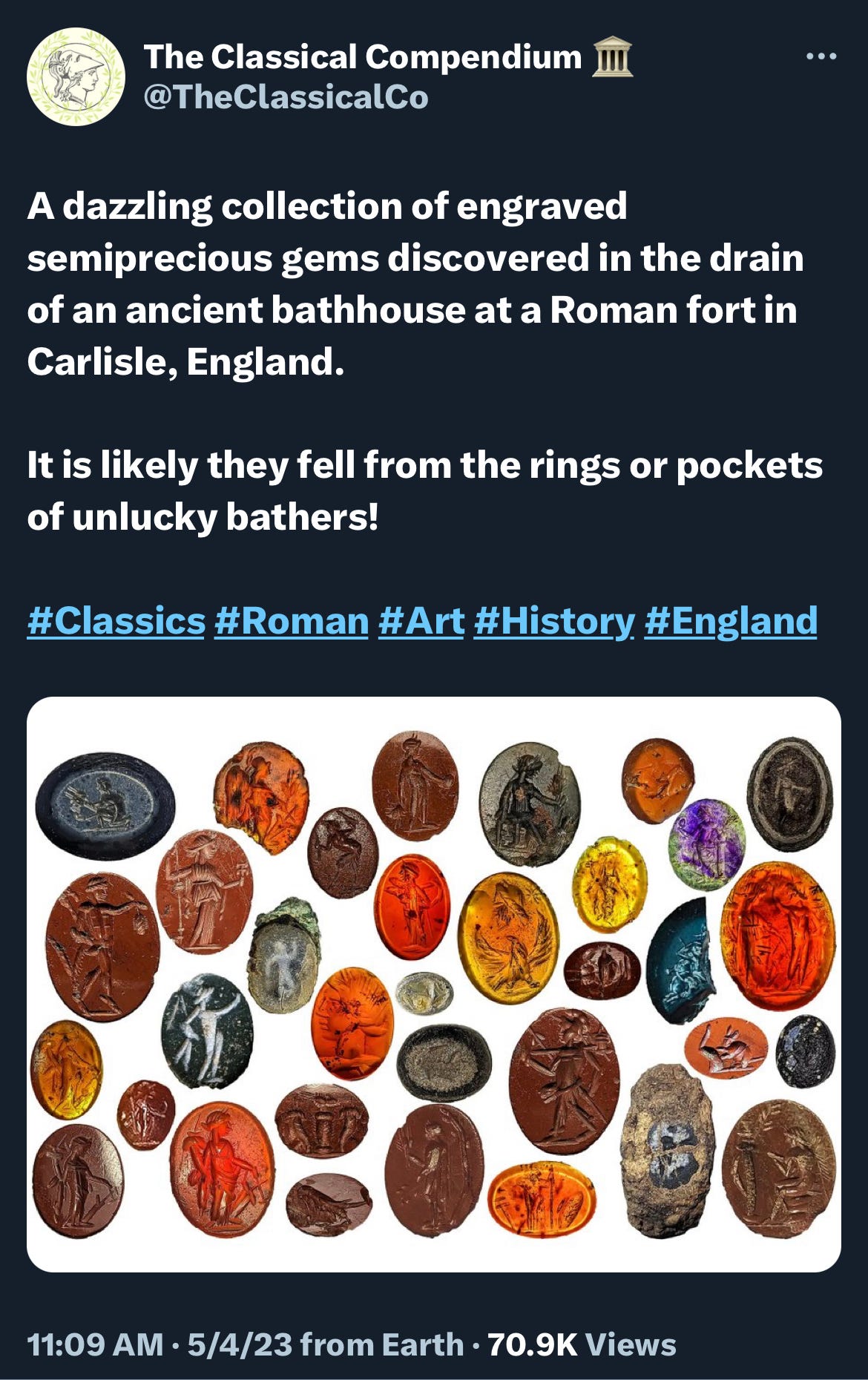

With summer and days poolside just around the corner, consider this tweet a reminder from an ancient Roman bathhouse—make sure your semiprecious gems and other jewelry don’t end up in the pool drain! Elite-world-problems!

If you’ve never paid much attention to ancient intaglios before, they are worth your time. These were items of jewelry that carried a personal meaning for the wearer, and you can spend lifetimes studying the variety of depictions and skill of the ancient gem engravers. You can learn more about ancient engravers on the Getty Museum’s website, and watch a modern engraver carve a gemstone using ancient techniques (although they do expedite the process by skipping the hand-powered drills in favor of a power tool) in the video below.