Ancient/Now - March 20th

A hieratic papyrus from Saqqara, the debate over a Roman wooden phallus, elite homes in Chichén Itzá and more

First and longest hieratic papyrus from Saqqara

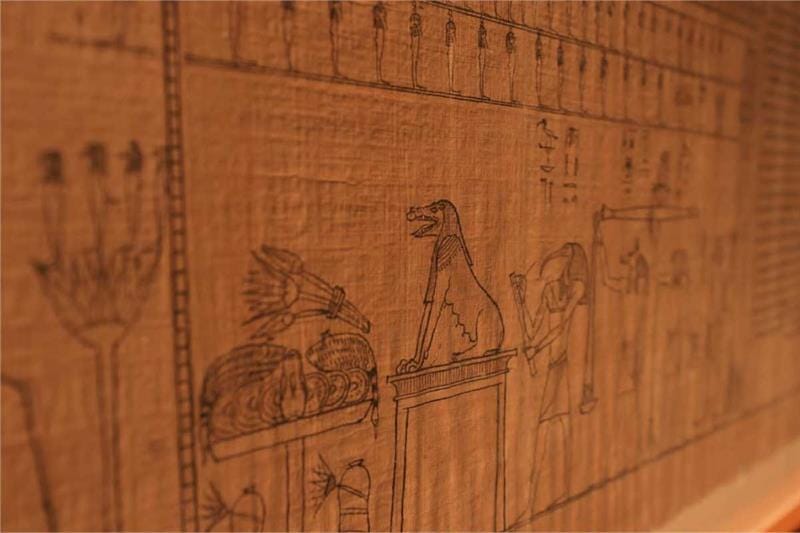

Known as Papyrus Waziri I, the first and longest hieratic papyrus discovered at Saqqara’s necropolis is now on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. The unrolled papyrus is a whopping sixteen meters long and the museum’s experts spent over eight months documenting and conserving it. Found in good condition during a May 2022 mission of the Supreme Council of Antiquities at Saqqara, the papyrus records 113 chapters of the so-called Book of the Dead in 150 columns and was discovered inside the cartonnage coffin of a man maned Ahmose and dates to the early Ptolemaic period. Notice that Books of the Dead got longer as Egyptian civilization got longer, as if Egyptians became increasingly worried about leaving anything out.

Darning tool or ancient Roman phallus?

I mean, one should be able to tell a clothes making tool from a dildo, right? Well, last month in an article published in the Cambridge University Press journal Antiquity, archaeologists Rob Collins and Rob Sands posit that a 6.3 inch oblong-shaped wooden object discovered at the Vindolanda Roman fort in England should be reclassified as an object of pleasure and not a darning tool, as was first suggested when the object was found in 1992. Located in northern England near Hadrian’s Wall, the Vindolanda Roman fort is known for its anaerobic conditions, which have preserved artifacts made of materials like wood and leather that would have severely decayed in a more oxygenated environment. The wooden phallus was discovered in what amounts to a trash pit at the site, so the archaeological context does not fully settle the debate as to the use of the object. They suggest two possible uses for the object other than use as a “sexual implement,” including the possibility that it was part of a herm or functioned as a pestle. The authors go on to note that,

Stone and metal phalli are known from across the Roman world, but the Vindolanda example is the first wooden phallus to be recognised. Combining evidence for potential use-wear with a review of other archaeological and contextual information, the authors consider various possible interpretations of the function and significance of the Vindolanda phallus during the second century AD.

Use wear! From what kind of activity we might wonder… Furthermore, the researchers observed:

Tactile examination of the Vindolanda phallus reveals that the convex base end is smooth, which we attribute to intentional shaping during manufacture and/or exposure to repeated contact through use.

While you consider that bit of tactile evidence, try to avoid picturing archaeologists in a future century sorting through an archaeological deposit consisting of the contents of your bedside table, debating with thoughtful interest the function and use of all that they find there. And let us just say the obvious here at the end: as a group of women experts of antiquity, that notch at the end of the device would not be very comfortable for use as a dildo.

Elite residences at Mexico’s Chichén Itzá

Archaeologists for the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) have uncovered a new group of structures they believe were once residences for the elite at the Mayan site of Chichén Itzá in Mexico. These residential structures are the first housing complex of any kind discovered in the ancient city and are of such size and quality that INAH archaeologists suggest it could be “the first residential group where a ruler lived with his entire family.” It’s interesting that elites got special housing, but also that they may have had central, communal living imposed upon them by their ruler. A gilded cage, perhaps? Archaeologist José Osorio León speculates,

“There must be more residential groups that have not been explored yet,” he tells Reuters. “The study of these peripheral groups, around the central part, could tell us about other families, other groups that made up this great city.”

Such a discovery will certainly improve our understanding of a site considered one of the Seven Wonders of the World, but it is also a reminder that much of our knowledge of the ancient past is biased toward the elite because we focus on sites with monumental constructions. Never forget that the majority of people in ancient societies lived and died leaving little evidence in the archaeological record.

Bioanthropological evidence for the earliest horsemanship

How can archaeologists tell that people domesticated and rode horses? In an article published this month in the journal Science Advances, a group of researchers published their findings related to the origins of horseback riding. Domestication of the horse dates to somewhere around 3500 to 3000 BCE, and this is visible in the horses bones. But determining exactly when humans began riding horses—rather than just attaching them to carts and chariots—has proven much more difficult. Because it was often made of materials that easily decayed (such as wood or leather), evidence for horseback riding such as saddles, bridles, etc. did not survive over long periods of time. If we determine the domestication of the horse from their skeletons, maybe we can prove human horse riding by looking at human skeletons. For instance,

Alterations associated with riding in human skeletons therefore possibly provide the best source of information. Here, we report five Yamnaya individuals well-dated to 3021 to 2501 calibrated BCE from kurgans in Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary, displaying changes in bone morphology and distinct pathologies associated with horseback riding. These are the oldest humans identified as riders so far.

In other words, these researchers have identified the remains of horseback riders by examining the ways in which riding horses altered their bone structure. Studying osteological remains of a people known as the Yamnaya, who lived in the areas encompassing portions of modern Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary, researchers identified six skeletal traits that indicated “habitual horsemanship.” Remember, bioarchaeologists can tell if a woman has given birth from examination of her skeleton; same for horse riders, apparently. They suggest that the Yamnaya were horseback riders as early as the third millennium BCE.

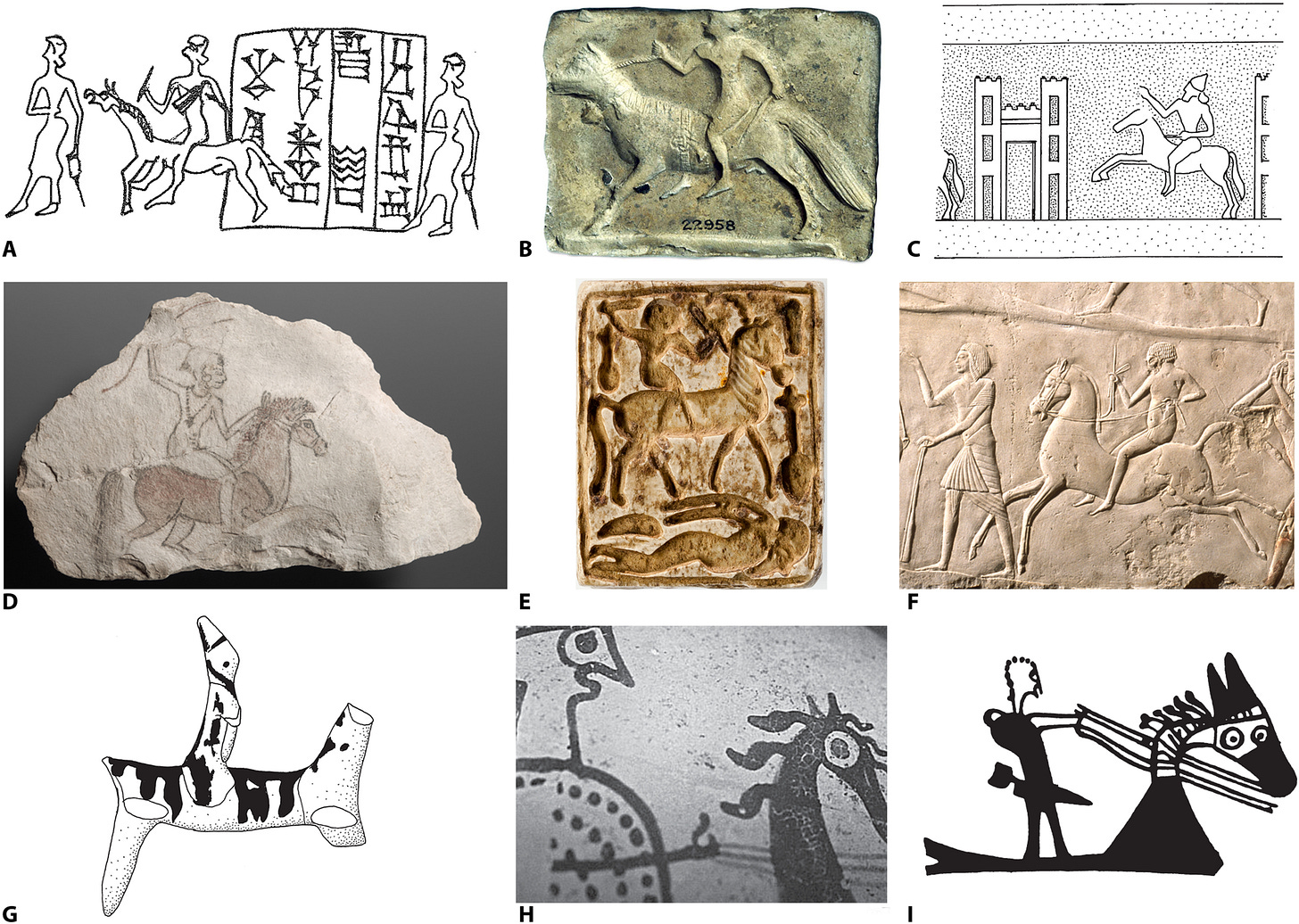

Biomechanical stress markers on human skeletons provide a viable way to further investigate the history of horseback riding and may even provide clues about riding styles and equipment. Depictions of Bronze Age riders (Fig. 5) usually show a position called “chair seat.” This style is mainly used when riding without padded saddle or stirrups to avoid discomfort to horse and rider. It is physically demanding, with the legs exerting constant pressure to cling to the mount’s back and needs continual balancing, but would not preclude activities such as combat or the handling of herd animals, as numerous historical examples demonstrate. The osteological features described here fit well with this riding style and may have been typical for the earliest period of horsemanship.

While debate regarding the origins of horseback riding may continue (see Wegner and Cahaill’s argument about Senebkay’s skeleton found at Abydos!), this research is another example of the ways in which bioarchaeolgoical evidence expands our knowledge about ancient people.

A 1.2 million year old Ethiopian obsidian axe factory

A team of researchers, publishing in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, discovered a obsidian handaxe workshop dating back to 1.2 million years at the site of Melka Kunture in Ethiopia—the earliest (by a lot) example of obsidian shaping. This is the only workshop dating to the Early Pleistocene period. The shaping techniques were highly regularized indicating a “culture” of knapping.

Knapping obsidian is a “cognitive leap,” according to the authors, when ancient humans adapted previous flint knapping skills to the more challenging obsidian stone. Obsidian is volcanic glass after all; you try striking that and creating a perfect blade…

A note to our subscribers

This month Ancient/Now passed 1,000 subscribers! Thank you for subscribing and being a part of our online community. Please continue to like and share our posts and tell your friends about us! We would like to express special gratitude and appreciation to those of you with paid subscriptions. You support our work—we can pay Amber! we can pay Jordan!—and make it possible for us to continue to share our ancient historical perspective on current history and archaeology related news through this Substack.