Ancient/Now - January 20th

Nubian archaeology, an ancient Chinese emperor's lethal booby traps, familial intermarriage in Minoan Crete, ancient prosthetics and more

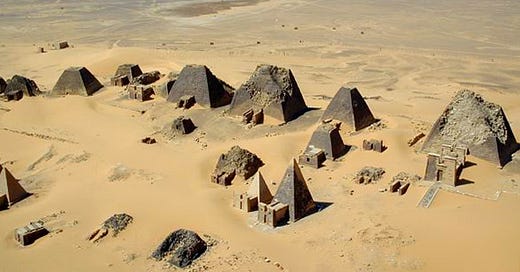

Upcoming Event: “Understanding Ancient Nubia from Antiquity to Today”

Tomorrow the Getty Villa is hosting a lecture on ancient Nubia by archaeologist and University of Chicago Ph.D. candidate Debora Heard. Specializing in Nubian archaeology and the history and language of ancient Egypt, Dr. Heard’s lecture will cover the history of Nubia and why the study of this ancient culture and the significance of its history has been neglected and largely excluded from the popular historical narratives. The event is free and will take place both in-person and via Zoom, but you need to register for tickets or online access. Those attending in person will also be able to check out the current Getty Villa exhibition Nubia: Jewels of Ancient Sudan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, on display until April 3, 2023.

Lethal Booby Traps in the Tomb of China’s First Emperor?

Do booby traps like rivers of mercury and loaded crossbows await any archaeologists who dare to enter the tomb of China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, as one ancient account warns? Thus far archaeologists have chosen not to find out.

You are probably familiar with the so-called “Terracotta Army” discovered in the mausoleum and surrounding necropolis of China’s first Qin emperor. The eternal duty of this clay army was—is?—to protect the dead ruler and the treasures tucked away with him in his tomb. While large portions of the mausoleum surrounding Qin Shi Huang’s tomb have been explored and the realistic, amazingly detailed and well-equipped Terracotta Army studied, archaeologists have thus far hesitated to breach the emperor’s tomb itself. However, the ancient warning of booby traps is in some ways the least of their concerns. First and foremost in every archaeologist’s mind is the reminder that, even when done carefully and keeping meticulous records, archaeology is an act of destruction. For now scientists and archaeologists are holding back from opening the tomb in the hope of finding a non-invasive way to explore the tomb, a way that will provide them with more information but keep the tomb intact and untouched. The restraint of these archaeologists is admirable—can you imagine Howard Carter or Heinrich Schliemann leaving the tomb of Tutankhamun or the treasures of the city of Troy untouched for future generations of archaeologists with better technology to explore?

Although there are solid methodological and archaeological concerns behind archaeologist’s hesitancy to open the emperor’s tomb, one can understand why the ancient account of the tomb’s supposed lethal protections might give one pause. Writing a century after Emperor Qin Shi Huang was interred (ca. 210 BCE), Chinese historian Sima Qian produced the only surviving description of what the tomb of the emperor holds:

"In the ninth month, the First Emperor was interred at Mount Li. When the First Emperor first came to the throne, the digging and preparation work began at Mount Li. Later, when he had unified his empire, 700,000 men were sent there from all over his empire. They dug through three layers of groundwater, and poured in bronze for the outer coffin. Palaces and scenic towers for a hundred officials were constructed, and the tomb was filled with rare artifacts and wonderful treasure. Craftsmen were ordered to make crossbows and arrows primed to shoot at anyone who enters the tomb. Mercury was used to simulate the hundred rivers, the Yangtze and Yellow River, and the great sea, and set to flow mechanically. Above were representation of the heavenly constellations, below, the features of the land. Candles were made from fat of "man-fish", which is calculated to burn and not extinguish for a long time.”

All we really want to know at this point are what “man-fish” fat candles look like…..

Familial intermarriage “unprecedented in the global ancient DNA record” revealed in Minoan Crete

First, let’s just point out that DNA studies have been horribly misused to claim land, to exclude people, to bolster nationalism and racism in all kinds of ways. That being said, a recent study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution outlines the findings of a study of the DNA record of the prehistoric Aegean and notes the discovery of a “consanguineous endogamy practiced at high frequencies, unprecedented in the global ancient DNA record…” What in gods’ name does this mean, you might ask! Well, the DNA evidence suggests that in this population’s marriages were determined by kinship relationships, encouraging incestuous reproduction, rather than excluding it. The genome analysis specifically indicates that it was common for first cousins to marry in this community. Over a thousand genomes from around the world have been studied previously, but this is the first study to feature analysis of Aegean genome data from the Neolithic to the Iron Age (the data was comprised of 102 ancient individuals from Crete, the Greek mainland and the Aegean Islands).

"More than a thousand ancient genomes from different regions of the world have now been published, but it seems that such a strict system of kin marriage did not exist anywhere else in the ancient world," says Eirini Skourtanioti, the lead author of the study who conducted the analyses. "This came as a complete surprise to all of us and raises many questions."

Researchers speculate that one possible reason for such close intermarriage among kin was a way to ensure land ownership stayed within the family. As Kara discussed in When Women Ruled the World, the ownership and inheritance of property is a primary concern within agricultural patriarchal societies in particular and shapes the social rules surrounding sex (including the concept of female virginity) and marriage. This genomic data comes from the Neolithic, through the Bronze Age, and on to the Iron Age, exactly when competition over scarce agricultural and grazing land would have been established and ramped up.

We know that the biological dimensions of societies and cultures, both ancient and modern, throughout the world often included various degrees of intermarriage within families. Incest allowed people to keep wealth in the family! Certain ancient Egyptian royal dynasties were famously incestuous; familial intermarriage and incest is mentioned in some Biblical narratives, and the history of intermarriage among in European royalty is well-known (think Charles II of the Habsburgs!), just to name a few examples. Although we can get information regarding kinship in various societies through the historical record, scholars don’t always have the luxury of a genomic study to help fill out the biological profile of a population, particularly for prehistoric societies. As technologies improve and more genomic datasets are analyzed, it will be fascinating to see what cultural insights they have to offer on the biological composition and familial structures of past populations. And may we end with a salient point: it’s extraordinary how nascent capitalism (hoarded domesticated animals and plants!) got people to give up tried-and-true sexual taboos that encouraged a genetically healthy population. In case you needed any more evidence, capitalism does not create healthy humans…

The ancient origins of prosthetics

Amputations and prostheses are as old as warfare itself, and this article by Jane Draycott, Lord Kelvin Adam Smith, Research Fellow in Classics: Ancient Science & Technology, University of Glasgow, offers insight into prosthetics in ancient Greece and Rome. Ancient soldiers were more susceptible to limb injuries that still plague modern soldiers such as high-velocity penetrating projectiles, frostbite, trench foot, and more. Hell, even Prince Harry just revealed his own frost bitten phallus (say it three times fast). Seriously injured soldiers in the ancient world did not survive such trauma, but the Greek historian Herodotus provides evidence that around the time of the Greco-Persian Wars (499-449 BCE) soldiers started to benefit from orthopedic surgeries like minor amputations. (Major amputations of an arm or a leg were still incredibly dangerous because of those pesky arteries.) Around this time we have new evidence of prosthetics in ancient Egypt in the form of well-worn big toes made of wood and/or cartonnage found on the feet of mummies. The next advancements in safer amputations and prosthetic technology occurred in the Hellenistic period (323-31 BCE). Draycott attributes these medical and orthopedic advancements to the community of ancient scholars studying at the Library of Alexandria, sharing their knowledge and discoveries:

“These advances were thanks to medical practitioners at the Museion and Library in Alexandria making in-depth anatomy studies by dissecting and even vivisecting criminals sentenced to death.”

Today’s modern technological advances in prosthetics, no doubt driven by the traumatic injuries of soldiers in Iraq and Afghanistan, improve the quality of life for veterans and civilians alike, just as they did in the ancient world. Then, as now, those advances were the result of collaborative efforts of medical experts, artists, and the latest technology.

The opulent home of two freed Roman slaves restored

The ancient city of Pompeii in Italy is the archaeological gift that keeps on giving. The entire city of Pompeii was preserved in a moment in time by a massive volcanic eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 CE, and archaeologists have been working since the 19th century to excavate, preserve, and restore uncovered portions of the city. One of their latest restoration efforts is the so-called “House of the Vettii,” an opulent villa that experts have been conserving and analyzing for the past twenty years. The villa’s owners, Aulus Vettius Restitutus and Aulus Vettius Conviva, are believed to have been freed slaves who made their fortune in the wine trade. (Of course, it was wine!)

“This is the house which tells the story of Roman society,” Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of the Pompeii archaeological park, tells the Guardian’s Angela Giuffrida. “On the one hand you have the artwork, paintings and statues, and on the other you have the social story [of the freed slaves]. The house is one of the relatively few in Pompeii for which we have the names of the owners.”

Filled with eye-popping, brilliantly colored frescoes with mythological and erotic themes that speak to the owners’ desire to show off their wealth and earned place amongst the elite of Pompeiian society, the “House of the Vettii” is again on view to the public. Fieldtrip!

Webinar: Secrets of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom Capital: el-Lisht

Next month Kara will moderate a webinar featuring a lecture on the Middle Kingdom capital of ancient Egypt by Egyptologist Sarah Parcak (University of Alabama at Birmingham) and participate in a post-lecture Q&A. Members of the general public can register for the event for a small fee. All proceeds from the event help fund ASOR’s scholarships and online resources.

Lecture: Kara talks about her book, The Good Kings

Earlier this week Kara spoke for the “AIA Archaeology Hour” and discussed her book, The Good Kings: Absolute Power in Ancient Egypt and the Modern World. Extraordinarily, she was reasonably well behaved and didn’t say any bad words, although she was very woke…