Ancient/Now - December 16th

Fascinating fakes, Neolithic phallic narratives, the collecting history of "pure piracy" by U.S. museums, ancient Mayan diplomacy, and more

Why are we so fascinated by art fakes?

If you’ve ever taken a gallery tour in a museum, you may have heard one of the most common questions visitors ask educators: “Is it real?” This BBC article explores the trend of museums intentionally displaying art “fakes” that were once thought to be genuine works of art by famous artists, as the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. did with their exhibition Vermeer’s Secrets. New technology is revealing that while some paintings originally thought to be Vermeer’s work were honest efforts by associates or students attempting to emulate the master’s style, other paintings in the exhibition were outright fakes meant to deceive. As it turns out, whether a work is an imitation, forgery, or genuine it can help art historians paint (see what we did there?) a more complete history of the past.

Oldest known depiction of a (public) narrative scene is a carving of a man holding his penis

Of course it is. The 11,000 year old carved panel, which appears to depict sequential narrative scenes—kind of like a comic book strip—of humans interacting with animals, was found in Sayburç (southeastern Turkey). There are older so-called “storytelling” scenes such as the cave painting in Lascaux, France (17,000 years old) and the Indonesian island of Sulawesi (44,000 years old), but this Neolithic carved panel in Turkey is distinguished by its location in what would have been a public place. Such a public placement suggests that this artistic representation may have been used as a way to pass on a story and/or tradition. You can read Eylem Özdoğan’s archaeological report on this discovery, just published last week by Cambridge University Press, on their website.

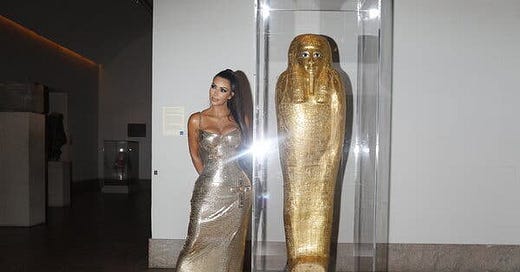

“My collecting style was pure piracy” — NYT: the “Indiana Jones” era of collecting for U.S. Museums is over

Today law enforcement and foreign governments are putting more pressure than ever on U.S. museums to return looted art to their countries of origin, but there are critics who wonder what the cost of such a policy will be. Attitudes toward museums and looted art shifted over a decade ago, but recently a real push has been made to pressure U.S. museums to return stolen art. And most interestingly, museums have felt compelled to comply. The J. Paul Getty Museum, the Denver Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art have all recently returned artifacts in their collections that were stolen. Some of these objects, like the three terracotta figures the Getty recently returned to Italy, represented some of the finest works of art and mainstays of museums’ collections. Past collecting practices of U.S. museums relied so heavily on looting and other unethical methods that if every stolen artifact held in U.S. museum collections were returned, the galleries might look quite barren compared to the way they’ve looked in the past.

Should U.S. audiences, they [critics] ask, be deprived access to iconic objects that they suggest belong, not to individual nations, but to humankind?

More people will see the Benin bronzes in New York than in Benin, critics argue. (For more on this topic of increasing public access to cultural heritage, check out Amber’s June post on virtual exhibitions and archaeological reproductions.) Some groups have even made legal moves in an attempt to prevent some artifacts from being repatriated. Many experts find such a question a result of outdated, patriarchal, patronizing thinking. Meanwhile, those interested in finding collaborative solutions have struck agreements, such as the one between the Met and Greece, that will allow a privately assembled collection of Cycladic art to remain on display in New York but transfer ownership to Greece. As for us, we think the Humankind Benefits From Looted Art is an All Lives Matter defense that serves the dominant class.

The Netherlands returns over 200 pre-Hispanic artifacts to Mexico

While it may be a major contributing factor to the fall of civilization as we know it, the power of social media can also be used for good. Back in 2018 the #MiPatrimonioNoSeVende (“My heritage is not for sale”) was begun by Mexican President Andres Manual Lopez’s administration has helped the Mexican government repatriate some 9,000 artifacts to Mexico, including 223 artifacts returned by Dutch government earlier this year. These kind of success stories are heartening as the global community continues to grapple with the legacy of cultural exploitation, colonialism, and repatriation of artifacts to their countries of origin (see above story).

A story of ancient diplomacy in the Americas told through a spider monkey’s remains

The ancient city of Teotihuacan, located outside of modern Mexico City, was the site of a 2018 discovery of a 1,700 year old spider monkey skeleton buried next to an eagle and some rattlesnakes at the base of a pyramid (as one does). Researchers who reported their discovery of these remains last month at the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences have posited that because there is no archaeological evidence for primate sacrifice in Teotihuacan, the spider monkey may have been a diplomatic gift from elite Mayans to the people of Teotihuacan. This discovery is a fascinating look into the mostly peaceful (but sometimes violent because humans) relationship between the people of Teotihuacan and the Mayans.

The rise of a Mayan royal dynasty may have taken generations

One does not simply establish an authoritarian royal dynasty overnight—it takes a village; it takes time. Archaeologist and epigrapher Markus Eberl of Vanderbilt University in Nashville and his fellow researchers have published new evidence that suggests that the Mayan royal dynasty founded at Tamarindito (located in modern Guatemala) may have taken a century and a half to attract followers and subjects. While ancient Mayan royal sources indicate rulers had absolute power, the archaeological evidence at Tamarindito tells a complicated story of a royal dynasty that began with a few dozen people and that took over a century to negotiate and legitimize themselves into becoming an authoritarian power. The example of Tamarindito reminds us that authoritarians cannot come to power alone, but must be supported by a social network of supporting elites choreographing the establishment and legitimization of their authority—and maintaining it and benefiting from it. Sounds familiar, yeah? That’s because patriarchy…

Did you enjoy our post?