Ancient/Now - April 26th

Netflix, controversy and Cleopatra VII, piecing together an ancient Greek kylix, the ethics of researching ancient DNA, and more

Netflix, Controversy and Cleopatra VII

The upcoming Netflix documentary Queen Cleopatra, produced by Jada Pickett Smith, has once again stirred up the forever controversial and impossible-to-resolve question about Cleopatra VII, her ethnicity and skin color, and a myriad of opinions on how she should be cast in a film production. Ironically, Hollywood’s perennial efforts to give voice to her story often end up generating a cultural debate that distracts from it. In this instance, some people (for example, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass) are reacting negatively to Cleopatra being portrayed by a black actor and/or arguing that such casting forgets that she was Greek. There is even a Change.org petition to cancel Netflix’s Queen Cleopatra because it “falsifies” history by casting a black actor as Cleopatra VII. (Where were these people who are so upset about the falsification of history when Netflix released Ancient Apocalypse??) This question and debate about skin color comes up every time a new Cleopatra is cast (as it did when Gal Gadot was cast in an upcoming Cleopatra movie), and since Hollywood’s obsession with her story is as strong today as it ever was, that means it comes up a lot.

Ultimately it is an exhausting and frustrating topic for scholars of the ancient world because the question of Cleopatra’s skin color can never be answered, is unimportant in so far as social perceptions of race and skin color are socially constructed in unique and complicated ways specific to time and place, and it inevitably distracts from more substantive discussions of her as an historical figure. That being said, what is so very wrong with being black? Because we certainly seem to have less of an issue with Cleopatra being British-Isles-white. And given that Cleo VII found herself at the very end of her Macedonian dynasty, intermixing with Egyptians is to be expected. Who knows what her skin color actually was? Those who claim to know are deluding themselves.

If you are looking for an intelligent, expert discussion of this issue, you need to start by reading University of Toronto Associate Professor of Roman History Kathrine Blouin’s “Cleopatra VII: The Gift that Keeps on Giving” post on Medium. The gist of the matter, Blouin writes, is that

We have no clue who Cleopatra actually was as a person nor what she looked like. All our written sources are by non-locals, and to a great extent pro-Octavian men. I know this is a bit of a bankrupt comparison but imagine us knowing NZ PM Jacinda Arder not through her words and the words of the people she lived among and ruled, but through Fox News or The Sun’s lense. Let’s just say the reliability is … limited.

There is no way that the debate over Cleopatra’s skin color is going away any time soon, and in the end it does nothing to help us better understand Cleopatra VII’s role in history. Given that the Roman spin machine was at work on Cleopatra’s reputation and public image even before her death, there was never much of a chance that ancient historians would end up with reliable ancient sources about her life. In many ways these modern controversies and debates over Cleopatra continue the work of the ancient Roman propagandists who created an image and understanding of Cleopatra that reflected what they wanted people to see and understand about her. Seems we are still falling into the same traps…

Watch the trailer:

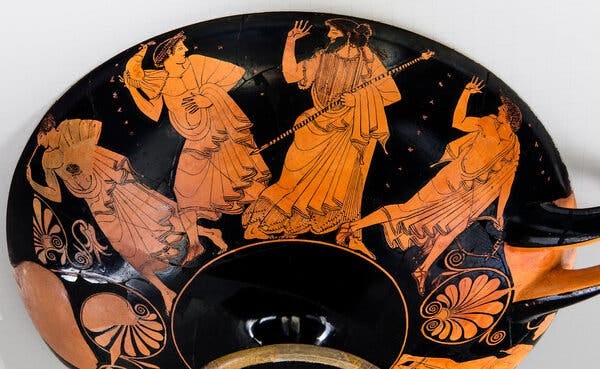

Piecing together an Ancient Greek kylix

From 1978 to 1994, the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired fragments of an ancient Greek kylix (drinking cup) from various art dealers. The Met identified the kylix and the work of the ancient Greek artists Hieron (a potter) and Makron (a painter) who made a significant artifact dating to around 490 BCE. Such restoration work takes patience, technical expertise, and expert-level puzzle-solving skills. And what luck! For a museum to be able to acquire the missing fragments they needed for one vessel in completely separate and unrelated acquisitions is akin to winning the lottery—multiple times. And yet, was it that lucky? In 2022 this kylix was seized by the Manhattan DA because it was identified as a looted object, and further investigation on the part of law enforcement led them to a startling idea.

They [law enforcement] suggest that the individual shards of the kylix, which had likely been found together, were knowingly dispersed among dealers who sold them separately to the Met, their small size deflecting the kind of attention a complete cup would have drawn.

Many experts believe the smuggling of illicit fragments became a black market routine. Some experts go further, suggesting that thieves at times smashed intact antiquities, destroying markers of history that had survived for millennia.

Some experts still argue that illicit antiquities dealers would never smash artifacts because they would have a much greater value on the black market as intact pieces. Perhaps they these researchers find it hard to imagine someone intentionally smashing intact ancient works of art to make a sale. But if you’re looking to make a profit, what is better—failing to sell an intact artifact because it attracts too much attention or smashing it into fragments that can be sold more easily?

What did ancient people make of ancient ruins?

Archaeologists in Mexico and Central America are beginning to develop a new perspective on how peoples of the precolonial past in Mesoamerica interacted with the ruins and artifacts of their ancient ancestors.

Previous generations of researchers tended to treat the massive ruins that dot Mexico and Central America as “inconsequential” in the lives of the people who lived nearby in later periods, Joyce [archaeologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder] says. Once a site emptied out and started to crumble, archaeologists typically concluded its importance had faded for people in the past. But a growing number are now recognizing that for people in precolonial Mesoamerica, “ruins, ancient objects, and ancestors were active parts of their communities,” says Roberto Rosado-Ramirez, an archaeologist at Northwestern University.

In particular, the powerful and elite in these precolonial cultures saw ancient ruins as an asset that could help legitimize their rule and connect them with rulers of the past:

Arthur Joyce, an archaeologist at the University of Colorado (CU), Boulder, has found they did so by putting their stamp on the ruins with a massive offering and portraits of themselves, set on top of the eroded surface of the old buildings. “These new rulers may have been trying to assert control over this thing that by its very existence would have questioned the inevitability and legitimacy of their power,” Joyce says.

This approach is quite similar to that of ancient Egyptian kings, who used and co-opted the sacred sites and monuments of their predecessors in order to legitimize and maintain their own power over the population and the landscape. Ramses II sent his son Khaemwaset to Djoser’s stepped pyramid complex to restore and add his name, for instance. One is also reminded of places like Mt. Rushmore in the Black Hills of South Dakota—a natural landscape that is still spiritually sacred to over twenty Native tribal groups and now, unfortunately in our opinion, bears the faces of four American presidents. The treatment of Mt. Rushmore—or the Six Grandfathers as the Lakota people call it—shows how later people can express ownership and rule over a place by brutally changing its form.

The ethics of researching ancient human DNA

Genetic research of ancient humans is a dangerous business. As paleogenomic research continues to advance and shed light on the genomes of our distant human ancestors and their migration patterns, some researchers are grappling with the potential ethical concerns raised by this type of genetic research. Any clinical human research today requires the consent of the participants and is regulated by institutional rules and government legislation. However, there are no such guardrails in place when it comes to studying the genomes of people who are not around to provide consent.

“Consent takes on new meaning” when participants are no longer around to make their voices heard, Bader [coauthor of an article about ethics in human paleogenomics in the 2022 Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics] and colleagues write. Scientists instead must regulate themselves, and navigate the sometimes contradictory guidelines — some of which prioritize research outcomes; others, the wishes of descendants, even very distant ones, and local communities. There are no clear-cut, ironclad rules, says Bader, now at McGill University in Montreal, Canada: “We don’t necessarily have one unified field standard for ethics.”

This issue is especially concerning for DNA studies of ancient Native populations (such as that of the ancient peoples of Chaco Canyon in New Mexico), who were the ancestors of living indigenous populations—because the ancients can’t give consent and because this DNA could be used to link or disassociate modern and ancient peoples to serve modern political agendas. (Link them with the ancients, one might be imposing a “primitive” identity on a modern tribe; disassociate them from the ancients, and the message might be that a modern tribe doesn’t have a claim to the land.) To begin to tackle such issues, some researchers have proposed “community-collaborative research” between experts studying ancient genomes and living descendant communities. The potential implications of paleogenomic research on these communities are still being explored, and conducting research in collaboration with living people seems to be one way to ensure that descendants of the populations being studied can stand in as representatives and speak for their ancestors.

What else were we reading this week?

This month National Geographic published an article Kara wrote on Neferusobek, who was—maybe?—Egypt’s first female king:

Was this woman Egypt's first female pharaoh? - Maybe… maybe not.

In March ARCE launched the Valley of the Queens and the Western Wadis on the Theban Mapping Project website - And we are excited!!

Menkaure Pyramid opens in June during Khufu closure - The Khufu pyramid has gotta close sometime to give it a rest from all the tourists’ carbon dioxide. Menkaure isn’t as awesome inside, but we can cope!

Researchers use 21st-century methods to record 2,000 years of ancient graffiti in Egypt. - Graffiti provide social historians with awesome info.

Tools for bleeding cows uncovered in 7,000-year-old cemetery - Gotta get your protein!

How did early modern European craftspeople pass on their knowledge? - And how might we do the same?

1,400-year-old mural of two-faced man found in Peru - Marvel comic of the day!

Roman-era trash dump containing naked Venus statue and other artifacts unearthed in France - But why would anyone throw naked Venus away??

7,000-year-old cult site in Saudi Arabia was filled with human remains and animal bones

DNA Confirms Oral History of Swahili People - Love it when oral histories can be confirmed!

In a Roman Tomb, ‘Dead Nails’ Reveal an Occult Practice

The untold history of the horse in the American Plains: A new future for the world

Their stories were lost to slavery. Now DNA is writing them - When you have no written history of ancestry paths, sometimes DNA is the only way.

Did Our Ancestors Actually Wield Clubs? Or what’s with the trope of the caveman and his club??

Oldest tartan found to date back to 16th Century

One more thing…

Kara was also a recent guest on the Chinwag Podcast with Paul Giamatti and Stephen Asma, where she discussed all sorts of Egyptology-related topics like aliens and the pyramids, death cults, Akhenaten, cats, and auto-fellatio—listen wherever you get your podcasts! In the YouTube version of the episode, in addition to the wide-ranging conversation you can watch their fun animations. (You can watch clips on here and here on Kara’s Instagram.) Check it out!